Meet a Fort Wayne artist building Hip-Hop culture in Southeast

Francisco Reyes is working to support his neighborhood with graffiti art and Hip-Hop culture.

Only a few blocks Southeast of shiny new developments and high-priced condos in downtown Fort Wayne, there’s a row of four humble houses on Euclid Avenue. The third house down has a large garden that takes up most of the front yard and extends into the lots next door. A spray-painted “Black Lives Matter” sign leans against the house, and there’s a large, old-school boombox on the front steps. Sitting behind the boombox is Francisco “Paco” Reyes.

He’s wearing a parody of a Fort Wayne Wizards t-shirt that he screenprinted himself for his brand/cultural movement, the Wrecklords. His black flatbill reads “INDELIBLE,” an adjective meaning “not able to be forgotten or removed.” And when you talk with Reyes, you quickly learn that this word describes both himself and his affinity for the Southeast side of town. This is his neighborhood, and he will not be moved.

Reyes refers to himself as an “American-Mexican”—not a “Mexican-American”—because while he is Mexican by descent, he’s lived in the U.S. his entire life. He and his mom bought the house on Euclid Avenue about 20 years ago when they moved to Fort Wayne from Los Angeles for the low cost of living and job opportunities.

“People here talk about the American Dream being on the coasts,” Reyes says. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, the coasts are cool, but for the same amount of money here, you can live like kings.’”

After buying their first house, Reyes and his mom purchased the vacant lots on both sides of their property and built their garden. Owning more land turned into the desire to revive their entire block, so they saved up to purchase the house on the corner, where Reyes currently lives.

Now, he and his mom are looking to buy the house in between their two properties. Reyes talks about turning his backyard into a “Graffiti Garden” to bring a taste of LA to the Southeast side of Fort Wayne.

But beyond the fulfillment of the so-called “American Dream,” his story paints a more complex picture of what it’s like to move to a mid-sized Midwestern city from a larger, more culturally diverse place on the coast. It’s a story that’s likely to become more common if, in fact, city-dwellers do flock to towns like Fort Wayne after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The cost of living may be lower in the Midwest and job opportunities may be plenty, but there’s still a matter of culture—what cultures are dominant and what cultures are lacking.

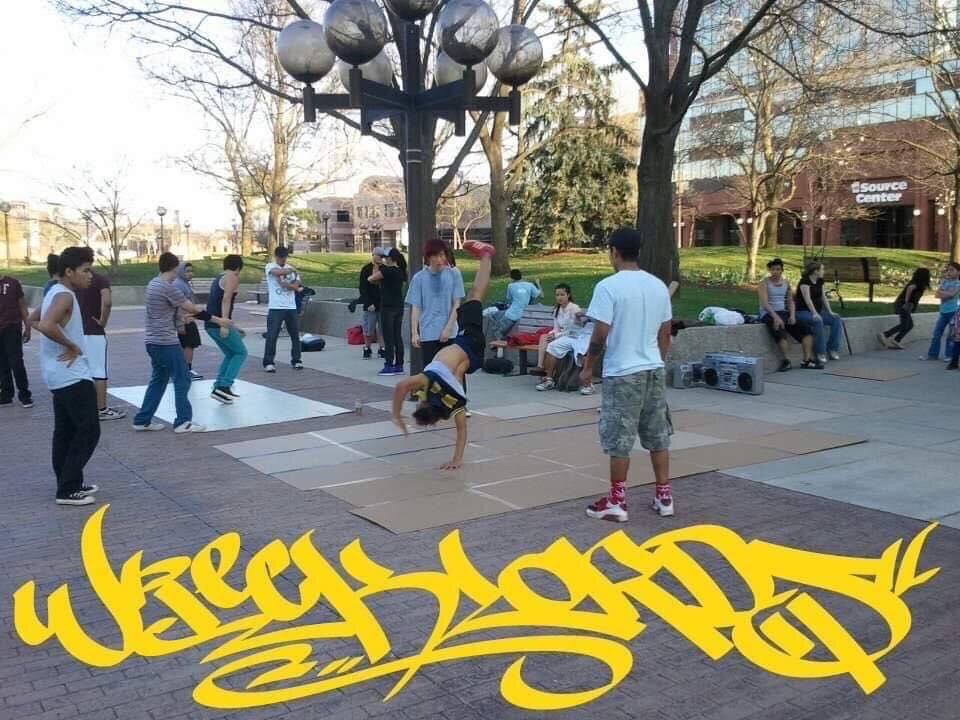

When Reyes first came to Fort Wayne, he didn’t connect with the buttoned-up, corporate business culture he saw projected in the city. Instead, he found himself missing the old school Hip-Hop culture he enjoyed in LA, complete with b-boy (breakdance) battles, graffiti art, and “park jams” with DJs spinning house music. But rather than complaining that he didn’t fit in, he took the initiative to bring more of his culture here.

“You just have to make your own niche,” he says. “Make yourself belong.”

It’s a philosophy he lives out as part of the Wrecklords, a group Reyes created in 2011 with his girlfriend Le Anne Fleming and their designer friend Rolando Green. The idea is to foster a culture around old school Hip-Hop in Fort Wayne, doing everything from designing merchandise to painting graffiti art, to hosting events, like b-boy battles and “park jams,” that draw hundreds of people to the South side of the city.

So what’s with the name? “Wrecklords” is derived from the Hip-Hop trio “Lords of the Underground” and their definition of a “Lord” as someone who masters a craft, Reyes says. In Hip-Hop culture, to “wreck” something means to do an outstanding job at it or to “kill it.” So the “Wrecklords” are those who are the masters of “killing it.”

“We master the craft, and we’re wrecking it because that’s what we do,” Reyes says. “We are the Lords of Wreck.”

But if you don’t know this, then you might assume the Wrecklords are a gang. That’s the mistake many people make when they think about Hip-Hop, Reyes points out. They assume it’s something negative, or it’s just gangster rap. But he and the Wrecklords are hoping to cultivate a different understanding of Hip-Hop in Fort Wayne—one that goes back to the scrappy, creative, “work-with-what-you-got” roots of it in the 1970s Bronx.

“We want to use Hip-Hop to help kids get better,” Reyes says. “We’re trying to give people a more positive view of it.”

More than music, Hip-Hop is often seen as a code of living among those who embrace it. It’s a code that involves using “whatever resources are available to create something new and cool,” and imitating the great works of others, but injecting personal style “until the freshness glows,” explains an article by the Kennedy Center.

Reyes shares a similar message when he talks about Wrecklords merchandise.

“We always had a motto with Wrecklords: ‘Put your culture on,'” he says. “In Hip-Hop, putting your city or your culture on means doing it properly and representing it well. We always liked that because it’s what we strive to do, so when you throw on a piece of Wrecklords apparel, we hope you’re putting your culture on while wearing it.”

In a way, Hip-Hop inspired a cultural movement about neighborhoods—”neighborhoods much of mainstream, middle-class America was doing its best to ignore or run down,” the Kennedy Center says. “Hip-Hop kept coming, kept pushing, kept playing until that was no longer possible.”

***

Reyes says the Southeast side of Fort Wayne is the only part of the city where he can imagine himself living. It’s the only place where he feels there’s enough counterculture to “mainstream, middle-class America” and enough loose restrictions to allow him, as an artist, to rise up and create something unique in Fort Wayne without politics, or red tape, or corporate culture getting in the way.

By day, he works for a print shop. But in his spare time, he’s working on a myriad of other passion projects for the Wrecklords and his neighborhood, like “terraforming” his backyard into a “Graffiti Garden” where he plans to put up walls and cover them in art.

“I’ve realized that what I’m doing with all the stuff I get involved with in Fort Wayne is that I’m assimilating the city,” he says. “When people talk about assimilating, as far as a cultural thing, they always say, ‘If you’re going to come here, you have to assimilate,’ but that’s not how traditional assimilation works. The invaders assimilate you.”

To assimilate the cultures he loves into Fort Wayne, Reyes operates on a simple philosophy: “You can wait on bureaucracy to help you, or you can start helping yourself, and then bureaucracy will want to help you because they can’t deny you,” he says.

He points to a concrete wall across the lot in front of his house where the Wrecklords are hosting a mural painting event this fall and next spring as part of the City’s Public Art Master Plan.

“I get to curate the art that will go there,” he says.

Reyes says he took the initiative to get the project started by reaching out to the wall’s owner and rallying support for the project. Then he reached out to the City to get them involved. Now, he’s seeking artists who haven’t done mural projects before to fill the space. He’s also hosting a temporary “open wall” mural this fall to let people who might not consider themselves artists to give it a try.

Along with assimilation, breaking down barriers to access and achievement in Fort Wayne is part of his goal, too.

“How else do you make public art democratized than by providing a space where everyone can paint?” he asks.

But while Reyes cooperates with City policies and procedures (for the most part), he typically operates independently from what he sees as a more corporate art scene downtown. Instead, he and the Wrecklords like to do their own thing on the Southeast side because they’ve found that other parts of town aren’t as receptive to assimilation.

***

About seven years ago, Reyes was commissioned to paint graffiti art on a catering truck for the upscale, New York-style restaurant and bar, Club Soda. But his artwork didn’t last long among the restaurant’s high-end, suburban clientele.

“They drove it into a subdivision for a catering event, and customers complained,” Reyes says. “They said, ‘We moved here to get away from graffiti,’ so Club Soda ended up repainting the whole truck white.”

Club Soda did not respond to a request for comments. Even so, Reyes says he’s not bitter about the experience. He actually finds it funny and all too common in the world of graffiti art.

“For me, that’s the best lesson I’ve ever learned in life through graffiti,” he says. “Nothing lasts forever. You get up as long as you get up, and that’s it.”

But while graffiti is transient by nature, the apparent lack of support for his artwork in wealthier, suburban neighborhoods of Fort Wayne speaks to a different divide in the city: The gap in social classes according to zip codes. Since the people in his neighborhood often operate in their own circles of influence and people in wealthier suburbs do the same, there are not many opportunities for residents of different social strata to intermingle and connect in Fort Wayne. As a result, there are frequent misunderstandings between groups, like the assumption that all graffiti is vandalism.

While the global Black Lives Matter movement is drawing attention to important racial disparities in Fort Wayne, Reyes feels that racism is only part of the problem his neighborhood is facing.

“When you go to the root of it, it’s classism,” he says. “The moment white people decided Black people were less than white people, it’s been a class issue. So how do we break that barrier is the question?”

It’s a question that comes to mind when he thinks about the future of Southeast Fort Wayne, too. While assimilation in its best forms allows diverse subcultures to coexist and enrich a place, assimilation in its worst forms turns into gentrification.

Reyes recalls friends whose houses were torn down as part of the effort to build Parkview Field downtown about 10 years ago. Now, he’s concerned that good intentions to infuse Southeast Fort Wayne with new life amidst the Black Lives Matter movement will result in the displacement of residents there—either by raising prices or changing the culture.

“How are we letting the people who live in Southeast know what’s available to help them instead of just trying to send in the troops and save this place?” he asks. “The trouble is: Not many of the troops know the villagers or how to build a hut.”

When he thinks about the best possible way for people to serve the Southeast side of town, he says it really boils down to the simple power of “showing up.” And not just showing up for photo opportunities, but showing up with the intentions to get to know the people and culture there—and trying to be a part of what they’re creating instead of trying to control it.