How can Northeast Indiana improve its health, equity, and economy? At the root is local food systems

With food insecurity and supply chain shortages on the rise during the pandemic, many say the time to change food systems is now. Here's what's happening in the region's local food movement.

This story is part of Input Fort Wayne’s Solutions Series, made possible by support from the United Way of Allen County, the NiSource Foundation, NIPSCO, Brightpoint, and others in Northeast Indiana. The 10-part, 10-month series explores how our regional community is addressing residents’ essential needs during the pandemic. Read the first story here.

***

“When people think of local food, they often think of farmers markets or farm-to-table restaurants, and those are very good aspects of it, but it’s about so much more than that.”

That’s Janet Katz, Founding Director of the Northeast Indiana Local Food Network, speaking to a crowd of about 100 (masked and socially distanced) people in September at the annual Local Food Forum & Expo held at Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Among the audience are people of many ages, races, and backgrounds—Amish farmers with long grey beards, Burmese refugees, nutritionists and dieticians at Parkview Health, elementary school administrators, political activists, nonprofit leaders, Black urban farmers, and aging rural residents. They have different cultures and ideologies, but they all have two things in common: They all live in Northeast Indiana, and they all care deeply about local food.

Some care because it tastes better. Others care because it’s healthier for you and the environment. Others are concerned that nutritious food is scarce in parts of the community. And others yet believe it simply makes smart economic sense to invest in local food systems in the long-term—as opposed to the outsourced, commodity-based, profits-over-people food systems that have been failing communities during the pandemic.

More accurately, these systems have been failing Indiana long before the first case of COVID-19 emerged.

“The pandemic revealed a lot of weaknesses in our current food system,” Katz says. “In many ways, it’s prompting important conversations about food.”

Since the pandemic began, food has become a top concern among Northeast Indiana residents and people across the U.S., resulting in an influx of emergency funding to food programs on the local, state, and national levels. However, meeting urgent needs during a crisis is only part of the puzzle. Another part is addressing the deeper, preexisting, systemic challenges with food systems in the U.S. And what many working in this space in Northeast Indiana are experiencing is the reality that it’s all related.

Take, for instance, the Double Up Indiana program, sponsored by the St. Joseph Community Health Foundation, with support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), United Way of Allen County, and Parkview Health. Prior to the pandemic, St. Joe had been addressing food insecurity among people who qualify for food stamps and those just above the threshold who are not able to afford or access healthy food.

Thanks to increased funding and focus during the pandemic, they’ve been able to expand their programs with Double Up Indiana, which doubles people’s buying power on SNAP/EBT produce purchases at local farmers markets and grocery stores. St. Joe and Parkview are also expanding their Our HEALing Kitchen cooking classes to increase access and education around healthy eating.

But unless you’re on the brink of food insecurity yourself, you might assume these initiatives are isolated acts of goodwill that have nothing to do with you—other than perhaps a generous donation of your time or money. You might assume these programs help “those in need,” yet don’t really make sense economically or aren’t sustainable.

However, when it comes to food systems and efforts to help people access foods that are fresh, healthy, and locally produced, initiatives designed to serve some can have powerful effects for nearly everyone in a region.

When you realize how deeply local food (or a lack thereof) is tied to Northeast Indiana’s healthcare, equity, and economy, you begin to realize that maybe what’s unsustainable—maybe what doesn’t make sense economically—is the way we’ve been doing things for the past 100 years.

***

Despite the pandemic’s many adverse effects, national food systems expert Ken Meter, President of the Crossroads Resource Center in Minneapolis, agrees with Katz that the crisis has been changing the way we think about food in the U.S. in a few positive ways.

Namely, it’s brought communities across the country to the realization that food and health are necessities every human deserves—not privileges only a few should enjoy. Why? Because preventative health measures, like eating the healthiest food, serve everyone better in the long run, reducing healthcare costs and strengthening communities and economies alike.

“During the pandemic, we’ve largely stopped asking whether people deserve healthy food,” Meter says. “We’ve adopted more of a mindset that we’ve got to get healthy food to everyone to keep everyone healthy.”

Another mindset Meter sees shifting across the U.S. is the realization that food relief will be required for more than just the immediate crisis, or until the pandemic is “over,” or even until five of 10 years down the road with the current food system in place.

“We’ve started to realize this is permanent,” Meter says. “We’re going to need food relief as long as we have inequality.”

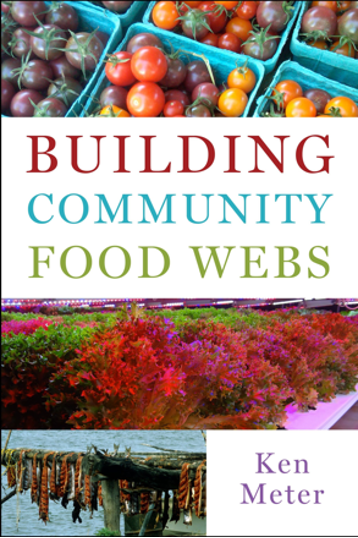

These realizations are not news to Meter, who has built his career researching and analyzing food systems across the U.S., including in Indiana. Earlier this year, he summarized his findings in a book called Building Community Food Webs, which traces a loss of $4 trillion of potential wealth from rural areas across the U.S. during the past 100 years and highlights various opportunities for reversing this trend.

“Our current food system has decimated rural communities and confined the choices of urban consumers,” the book says. “Even while America continues to ramp up farm production to astounding levels, net farm income (in 2018) is now lower than at the onset of the Great Depression, and one out of every eight Americans faces hunger. But a healthier and more equitable food system is possible.”

In two chapters of the book, Meter chronicles how leaders and farmers in Northeast Indiana, specifically, have taken steps toward building healthier, more equitable and localized food systems, waking up to the reality that Indiana’s need to address its food challenges is not merely a charity case, a nutritional incentive, or a smart move to prepare for future crises; it also presents a significant opportunity to make the state a more welcoming and equitable place, to engage immigrant and refugee populations in social mobility, to reduce healthcare costs, and to improve the overall economy.

“The current food system itself is creating inequality,” Meter says. “If you want to create greater equality, you have to change the food system.”

One of the most-cited findings from Meter’s research is that Hoosiers spend roughly $16 billion per year on food, yet more than 90 percent of these expenditures are going to farmers and producers out of state—even out of the country—when they could be going to local farmers and producers instead. When it comes to fruits and vegetables, that leakage increases to 98 percent.

Essentially, there is a $14 billion worth of economic opportunity in Indiana that could be realized if Hoosiers purchased most of their food from farms in-state. It’s data like this that convinced Adam Welch, Director of Economic Development at Greater Fort Wayne Inc., to get involved in Northeast Indiana’s local food movement.

“I remember reading some of the data in Ken Meter’s studies, and it blew my mind that while Indiana is the 10th largest farm state in the U.S., 90 percent of the food our residents eat is imported, and that economic impact is going to another state,” Welch says.

About the same time in 2016, Welch was also meeting with several people working in Fort Wayne’s agriculture sector, from farmers in rural communities to restaurateurs and lifelong local food advocates, like Jain Young of the Rose Avenue Education Farm for Burmese refugees.

But while the data was there, and while there were many active players in the local food scene, Welch also felt a lack of convening energy and focus around their collective goals.

“In my meetings, I would ask: Who’s leading this effort to support local food systems? And the answer was: ‘Nobody. That’s our problem,’” Welch says.

That is, until he met Katz and became part of the formation of the Northeast Indiana Local Food Network. Welch and Katz were both part of a steering committee formed by the Northeast Indiana Regional Partnership in response to Meter’s study. The committee was intended to strengthen communication and collaboration within Northeast Indiana’s local food economy, and the Local Food Network emerged as a result of this effort. Its mission is to “support the growth of a vibrant local food marketplace across Northeast Indiana, by increasing the visibility and economic opportunities for our region’s local food producers and businesses.”

Because Welch believes in the economic power of this work, he has stayed part of the organization ever since, where he now serves as Treasurer.

“One challenge in our region, when it comes to economics, is that we are still very set in our ways and focused on upfront, bottom-line costs,” Welch says. “I was kind of skeptical at first myself, but I’ve seen the way Janet works, and what her team is doing is very impressive.”

***

As Founding Director of the Northeast Indiana Local Food Network, Katz and her team are involved in many regional food initiatives, including new groups emerging to address challenges during the pandemic. While COVID-19 is increasing food insecurity in Northeast Indiana, it’s also driving some temporary, project-specific funding to organizations, like hers, that are typically resource-strapped and working to address monumental, systemic challenges.

A few recent developments Katz sees as promising in the region are the aforementioned Double Up produce programs at area farmers markets and grocery stores, extending access to local produce to consumers in more income brackets. Parkview Health’s Veggie RX program is another sign of progress, prescribing healthy eating tactics to patients as a form of preventative healthcare (with the knowledge that locally grown and eaten foods retain more nutrients than imported products.)

“These two programs are promising as they both improve access to locally grown produce and expand market opportunities for local produce growers,” Katz says.

The Local Food Network also has a few exciting projects of its own on the horizon, like its participation in a 10-member statewide coalition forming around local food and sustainable agriculture. This effort is led by the Hoosier Young Farmers Coalition and is hopeful that they will receive funding from the new Regional Food System Partnerships grant from the USDA. This state-wide partnership will expand Indiana’s value chain coordination, simplifying the process of sourcing food from local farmers and producers.

“What this value chain coordinator will do is facilitate communication,” Katz says. “They may or may not actually move product as a food hub would, but they will help facilitate communication and moving toward local food procurement—bringing producers, processors and buyers together so local food sales and purchases can take place.”

While convening roles, like value chain coordinators and Katz’s own position, provide critical connections needed to growing local food systems in Indiana, they also require sustained and substantial investment. The work of building stronger community food webs can be a nebulous, big-picture, long-term task, which doesn’t fit neatly into annual agendas or funding priorities, so finding support can be challenging.

In Northeast Indiana, the Local Food Network is still largely run by volunteers and services from part-time independent contractors. It receives funding from donors, sponsors, and grants. Since it was incorporated in January 2018, it has formed a 13-member board and is planning to apply for a 501c3 tax-exempt status in coming months.

Still, there is a significant need for greater support, Welch says.

“Janet has really taken on the job of four people, and she’s not taken much of a salary in her position,” he says. “While we are in a good place monetarily for a group like this, there’s still the need to take things to the next level and to hire some full-time, paid staff to alleviate the burden.”

While there is certainly a desire among Fort Wayne area restaurants, for instance, to source more of their products from local farmers and producers, there are also a multitude of challenges food system professionals face, like a lack of regional food infrastructure to package products and the price gap between local products and the products produced by large corporations receiving substantial tax breaks.

“To a person on the street who sees the data and the supply chain issues in our food system, you might think: ‘This doesn’t make any sense. Why wouldn’t we fix this?’” Welch says. “But the reality is that fixing the system is very difficult.”

One program illustrating—and attempting to address—local procurement challenges in Indiana is the Local Food Network’s own Farm to School initiative, in partnership with Parkview Health and Purdue Extension.

While the initiative is still in its early stages, Katz believes it is already helping more residents understand the benefits of sourcing food locally and making the process more approachable.

“It’s opening people’s eyes to the impact local food can have in our community,” she says. “And it’s providing examples that people can really wrap their minds around.”

***

When you hear the term “Farm to School,” you might picture farmers providing produce to school cafeterias. At least, that’s what Kylee Bennett imagined when she first heard it as Youth Wellbeing Coordinator at Parkview Health. But what she’s learned is that Farm to School is about so much more than procurement.

In her role at Parkview, Bennett helps regional children and families improve their health and wellbeing through educational empowerment and hands-on activities. About four years ago, several of Parkview’s partner schools began asking her about the Farm to School movement growing across the U.S. and how they could get involved.

That’s what prompted Bennett’s interest in the initiative, and what she’s learned is that Farm to School is about more than healthier meals. It’s also about educating students on food systems with classroom components on topics, like the value of local food and getting to know regional farmers. It even involves hands-on learning opportunities for students, like tending school gardens and taste-testing local produce to expand their palates.

In October 2019, Parkview Health received a USDA Farm to School Planning Grant, which resulted in Bennett being named the regional Program Director for the Northeast Indiana Farm to School team. Thanks to an additional 15-month grant from Indiana Grown (awarded to the Local Food Network), Bennett’s team has been able to pilot a Harvest of the Month program with more than 11 regional schools. This involves purchasing food from area farms to host monthly taste tests at schools as well as producing videos and classroom resources.

In 2021, Bennett’s funding partners received another two-year Implementation Grant from the USDA to expand their Harvest of the Month program and support more school partnerships and gardens.

“By the end of the two years, we plan to have 24 Harvest of the Month agriculture education videos completed with help of the Purdue Extension and the Northeast Indiana Local Food Network,” Bennett says. “Another component is we have funding to support some specific school districts in receiving a garden, which could be a raised bed or a tower garden indoors.”

Along with educating students and families about local food, Katz notes that Northeast Indiana’s Farm to School taste tests are providing additional revenue streams for regional farmers, too. As of October, the team has conducted taste tests with more than 3,000 elementary students across the region, purchasing items like peppers, carrots, apples, and cabbage in bulk.

The Northeast Indiana Local Food Network recently launched the Northeast Indiana Farm to School Fund to support the expansion of regional Farm to School programs.

“We already have more kids and schools who want to participate in Farm to School than we have the capacity to serve right now,” Katz says. “That’s a good problem to have.”

But good problems aren’t the only challenges with Farm to School. When it comes to procuring food for school lunches, Katz, Bennett, and other members of the team have encountered multiple hurdles, ranging from red tape from the Health Department in working with smaller producers to budget-strapped food service professionals at schools concerned about the cost and time it takes to source locally. Then there are the challenges facing smaller farmers in meeting an influx of demand from schools and working with academic calendars that don’t align with Indiana’s growing season.

Having studied Farm to School efforts across the U.S., Meter can attest that having robust education components to these programs is critical. Because when it comes to actually procuring the food, matters get much more complicated.

“I have worked with schools where the whole K-12 curriculum teaches students how to be agents for transforming the food system to a better one—that our job as consumers is to buy from local farms and facilitate stronger connections in the local community—and where the school itself pursues a mission of creating a more resilient food system,” Meter says. “Still, unless people are seriously committed to spending more money and taking more time, developing a sustainable procurement system can be a real challenge for schools and farmers, alike.”

Even so, amidst the onslaught of daily uncertainty and supply chain upheaval during the pandemic, some food service professionals in Northeast Indiana are convinced that sourcing more of their products locally is worth whatever it takes.

***

If you ask Becky Landes, the time for Indiana to start adopting Farm to School practices is now.

“If there ever was a time, it is now, because just the other Friday, it took me 60 attempts to order three days worth of food for my school district,” Landes says. “That’s a lot of time, and if I could be getting more food from local farms and companies, rather than ordering from large distributors, it would be much simpler.”

Landes is Director of Food Services for the Manchester Community School District about 45 minutes West of Fort Wayne. Her usually challenging job of providing meals for about 1,500 students has grown exponentially more difficult during the pandemic due to the pressure of shutdowns, virus spread, and labor shortages on the nation’s fragile, outsourced food supply chains.

Choosing to source local foods or to make foods from scratch used to be a luxury for her staff. Now, it has become a necessity because larger suppliers aren’t delivering. Prior to the pandemic, Landes and her kitchen crew of about 19 employees made roughly 25-50 percent of their food from scratch. Now, these figures have shot up to an estimated 50-75 percent.

“We couldn’t get enchilada sauce, and it’s on the menu on Monday, so now, my team is setting aside time on Thursday and Friday and adding this sauce to our already full load of meal preparation,” Landes says. “The situation is just constantly evolving, and it seems like no matter how hard we try, we can’t get ahead of our workload.”

One solution Landes has found to help fill gaps in her menu schedule is relying more heavily on the school’s pre-existing Farm to School relationships. Landes says Manchester is a bit ahead of the game in sourcing food locally and regionally.

“We’ve been doing Farm to School for 15 years now, to some degree, before it was even a thing,” she says.

This began when the district’s previous Food Service Director was approached by a local farmer who wanted to sell his vegetables to the school to stabilize his farm’s revenue stream after the rush of the summer market season subsided. Together, they developed a plan for offering a few “Local Food Days” during the school year. Since becoming the director herself, Landes has expanded the district’s local food procurement as she’s been able, sourcing products, like bread from South Bend, milk from Huntington, and local beef for hamburgers from Manchester’s own community.

“I can’t purchase 100 percent local, but I can purchase some,” Landes says.

This can-do mindset has made her one of the state’s go-to resources on Farm to School. She was tapped to join the state’s Indiana Grown for Schools initiative in 2018 and has since joined the Procurement team, which creates toolkits to help groups, like Bennett’s, trying to navigate Farm to School on the local level.

While procuring food from local farmers might still be a lofty ambition in many ways, wrought with challenges for food service professionals and farmers alike, Landes’s goal for getting involved is simple. She wants to bring both farmers and schools to the table with regional leaders and ask: Where can we begin?

Because she’s found that, many times, there are ways to get around roadblocks, like cost.

“Farmers often assume I can’t afford their product, and they might be right,” Landes says. “But often there is a compromise we can make.”

These calculated and creative decisions are part of the careful balance she and other Food Service Directors across the U.S. weigh in the process of converting some of their food to local sources. For instance, while Landes sources more expensive local beef for hamburger patties, she still uses cheaper varieties for lasagna, where there are more ingredients involved and less of a “wow factor.”

Since school food service providers are separate nonprofit entities (not owned by schools), they have strict and unforgiving budget requirements they must meet on meals—not to mention nutritional standards. On a typical school year, Landes’s team must provide meals for students at $2.50 each. That figure includes what she pays her staff in time, workers’ benefits, and other operational expenses. During the pandemic, her per-student allotment has risen to $4.60, thanks to an influx of funding. But rising food prices continue to make procuring local food a challenge.

Landes admits she’s not going to be a premium buyer for local farmers anytime soon. Even so, her orders are consistent, and she’s willing to work with them to develop plans that meet their needs and production capacities.

Before the pandemic, chicken was something she wanted to source locally, but she didn’t have the time to make it happen. Then, when she couldn’t get chicken from larger suppliers during the crisis, she found an in-state option at Fischer Farms in Celestine, Indiana.

That’s the advice she would give to other food service professionals and farmers interested in participating in Farm to School: Don’t try to do it all at once. Instead, take smaller steps toward greater goals as you are able. Start where you can. Plant the seed. Nurture it, and like the crops in due time, “it grows,” Landes says.