What is the value of a strong creative community? Ask these Indiana cities

Three Hoosier cities demonstrate how the arts impact a place's culture, economy, and talent prospects.

As COVID-19 threatens arts programs and creative culture in cities, having strategies to support the arts, as well as collaborative networks to share ideas is becoming increasingly important to leaders across the state.

That’s why for the past 11 years, the Indiana Arts Commission (IAC) has been encouraging communities to become designated Indiana Cultural Districts, says Anna Tragesser, Artist and Community Services Manager for the IAC.

While cultural districts are often known as anchor areas within cities that are saturated with arts programs and facilities, they are also more than that in Indiana, says Sean Starowitz, Assistant Director for the Arts for the City of Bloomington.

He believes the state’s cultural districts are unique nationally in that they have taken the extra step to ensure that creatives have seats at the table where decisions are made, allowing the arts to impact more aspects of community development in cities.

“It’s important in terms of how cities and towns evolve to make sure that cities provide arts and culture leaders with decision-making capacity,” Starowitz says, “because when arts and culture decision-makers are empowered, you can prevent the displacement of creatives.”

Long known as one of Indiana’s most creative college towns, Bloomington was among the first of 10 designated Indiana Cultural Districts in the state. But Fort Wayne and other Northeast Indiana cities have yet to make the list.

Tragesser says that while 40 communities in Indiana, including some in this region, have applied for the designation, achieving it is a high standard to meet.

“While many communities have strong arts scenes, Indiana Cultural Districts are being recognized for their deep commitment to sustainable cultural development,” she says. “What I mean by that is, just as communities have economic or community development strategies, these communities have strategies for maintaining creativity and participation in the arts.”

So why get strategic about the arts in your city? For Tragesser and others at the IAC, the answer is simple: The impact of the arts extends far beyond the surface level benefits of beautification and entertainment.

Here are three ways the arts are impacting cultures, economies, and talent prospects across the state.

Bloomington: Where the arts are restoring cultural memory

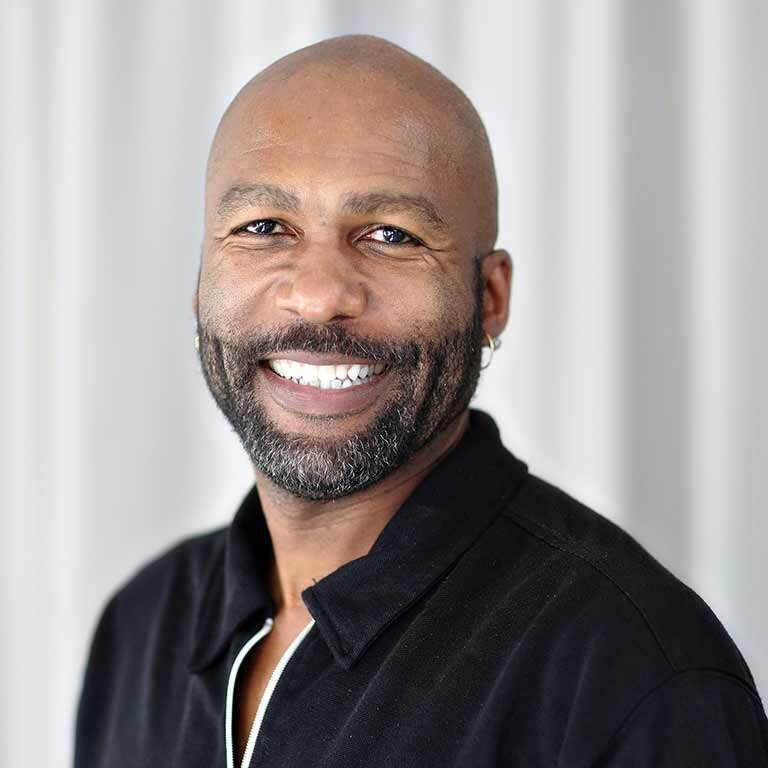

A few years after Stafford C. Berry Jr. moved to Bloomington to teach African American and African Diaspora Studies as well as Theater, Drama, and Contemporary Dance at Indiana University, he discovered a traumatic event in the City’s past had been displaced from its cultural memory.

In the fall of 1968, an Indiana University graduate named Rollo Turner opened a Black marketplace at the corner of Dunn and Kirkwood Avenues downtown, which became a peaceful gathering place for African American students and residents. But on December 26, 1968, the marketplace was firebombed by two members of the Ku Klux Klan.

“The entire inventory of the business was lost, and the Black Market was forced to close its doors permanently,” reports the IU African American Arts Institute.

Today, the site of the Black marketplace is known as Peoples Park. For the first few years of his employment at IU, Berry had driven past the urban park almost every day, and there was no physical marker or plaque to signify the marketplace or firebombing.

He began to wonder: How many people who pass through this park every day actually know about its history in relation to Black culture?

“As an African American transplant, that’s something I was really intrigued by,” Berry says.

As such, he applied for a grant with the Bloomington Arts Commission to put together a project in Peoples Park in September 2019 titled “Kuadhimisha,” which means “commemoration” in Swahili.

“I wanted to commemorate this particular historic aspect of the park and bring attention to the fact that this was a center of Black commerce,” Berry says. “I also wanted to highlight Black and African American culture through art.”

Calling together a few of his artist friends in the city, as well as students in IU’s drama and dance department, he put together a pop-up African dance performance, like a flash mob, which took over Peoples Park for one hour, complete with live music, dancers, and singers.

“We weaved in the history of the park, so folks were entertained, but also educated and reminded—or even informed—about the significance of this park for Black residents,” Berry says. “All kinds of folks who just happened to be there got to witness and take part in the commemoration.”

One of Berry’s students, Tyler Myles, who participated in “Kuadhimisha” is now an Associate Instructor of African American dance with him at IU, as well as an Arts Corps Fellow at the City of Bloomington’s Entertainment and Arts District. She describes the experience of “Kuadhimisha” as the opening of a conversation in Bloomington’s community.

Throughout the event, performers invited spectators to participate in African dances with them, using the artforms of music and dance to brooch subject matter that was previously unaddressed in their community.

“The space of Peoples Park carries a visible and physical weight in a lot of ways,” Myles says. “Some members of the Black community felt like the City never acknowledged the history of the area before, so (Berry’s) work has been foundational in terms of using the artistic practice as a way to impact and inform cultural memory, which is something a lot of art does.”

While “Kuadhimisha” has since inspired members of Bloomington’s community to work toward putting a physical plaque in Peoples Park, Berry sees the impact of the project as going deeper than the built environment. He believes that it has opened the hearts and minds of his neighbors, expressing emotions that would otherwise remain unspoken and presenting them to the broader community in a manner that they could be received.

“The arts open people up,” Berry says. “We’ve been taught that language is the way people communicate. But the wonderful thing about the arts is that they speak to us and open our person up to receive information that otherwise could not be communicated. It’s information that is not necessarily spoken in the form of a specific coherent language, but information that rides deep on feelings—on emotions, on thought, on deep-in-your-belly pangs that alert your body to change. The arts alert us to being vulnerable and to being brave enough to hear something we might not otherwise understand. The arts support us, so we can be sensitive.”

Jeffersonville: Where the arts are advancing small business and creative growth

When Andrew Just was dreaming up the idea for his business, Pearl Street Game & Coffee House, in downtown Jeffersonville, he knew that he wanted it to be a comfortable, communal space that brought together the best elements of a coffee house and a game store.

After traveling to other game-based bars and coffee shops in cities like Seattle, he designed his space to provide locally sourced baked goods and locally roasted craft coffee, as well as more than 60 board games to choose from. But when he first opened his shop about three and a half years ago, he still wasn’t sure how the Jeffersonville community would respond.

“It was kind of risky because there was nothing like it around here,” Just says. “I wondered: Will this work?”

Thankfully, since he, his wife Kim, and their business partner Jordan York opened Pearl Street, they have garnered a diverse clientele, ranging from extreme gamers, to casual coffee drinkers, and tourists from just across the river in Louisville, looking for something fun to do.

Just feels that his location near Jeffersonville’s up-and-coming NoCo Arts & Cultural District is contributing to this success, too—so much so that, last year, he came up with a concept to support the local arts scene.

While he has always displayed local artwork on his coffee shop walls, he took down his own art and transformed the walls into a six-month gallery/silent auction space for area artists, allowing customers to bid on about 24 pieces of original work. When the auction ended in September, 50 percent of the profits went back to each artist, and Just donated the other 50 percent to the NoCo Arts Center to support the renovation of its music studio.

Jay Ellis, Executive Director Jeffersonville Main Street, says that while Jeffersonville’s arts scene is still young, local leaders are starting to view the arts in a similar manner that they view historic preservation in revitalizing their downtown.

“The arts are economic development,” Ellis says. “That may not be what artists are thinking in their process, but the end result can be that art is a tool in our toolbox we can use to strengthen an area.”

Much like Just’s project at Pearl Street, the relationship between the arts and economic development is symbiotic.

“The arts bring people to the downtown area, and once they’re downtown, they see the businesses here, and they want to get something to eat or stop at a boutique,” he says. “They play off of each other very nicely.”

Madison: Where the arts are helping residents reimagine spaces and opportunities

When Indiana-based musician Jimmy Davis started working in Nashville, Tenn., his friends in the Music City couldn’t believe he was able to perform three or four nights a week in a community with fewer than 12,000 residents.

“It’s hard to play three or four nights a week in Nashville,” Davis says. “And yet, I’m doing that here.”

Here is Madison, Ind., a small, but culturally vibrant town on the Ohio River along the state’s southern border, which is quickly—and somewhat discreetly—establishing a reputation for itself as “Indiana’s Music City.”

“I’ve had lots of friends from Nashville come to Madison to perform, and it seems like every time, they just fall in love with this place,” Davis says. “The comment I’ve heard many times is: ‘Don’t let the word get out about your music scene here because people will come and mess it up.'”

With a penchant to tempt fate by putting Madison on the map, Davis has launched a project with his friend and fellow creative, Jane Vonderheide, designed to support local singer-songwriters in Madison and establish the city as a hub for music talent. Vonderheide is a visual artist who owns a barbershop in the city’s historic downtown called the House of Jane, so working with Davis, she created the House of Jane Songwriters Sessions, converting her space into an intimate listening venue for monthly performances, modeled after NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts.

“The mindset is: We have all this great music here, so let’s showcase that and introduce Madison to songwriters from out of town, too,” Davis says.

Since the House of Jane Songwriter Sessions launched in April 2019, its events have allowed about 35 lucky guests to cram into Jane’s 20- by 50-foot barbershop to hear a live performance, featuring one local musician from Madison and one out of town guest, playing 45-minute sets of original music each.

While the genres vary from country to rock, folk, jazz, and more, one thing artists can expect every time they take the stage at the House of Jane is the audience’s undivided attention.

“You can hear a pin drop at those shows,” Davis says. “In Nashville, you’re background music to people drinking beer. But at the House of Jane, your listeners are there to hear your art.”

Vonderheide charges a $20 cover fee at the door to pay the artists and sound tech and to produce a video of each artist’s work, which is given to them as an added bonus.

“So many artists are living week-to-week, just getting by,” Davis says. “Part of the deal to do the show is they get a complimentary video of their performance that they can use to get more work.”

Along with beefing up artists’ press kits, House of Jane also funnels them to other music venues around Madison where they can land additional gigs and enrich the local music scene. It’s all part of creating more opportunities for local and national artists to mingle, says Kimberly Franklin Nyberg, Executive Director of the Madison Area Arts Alliance.

“It creates the type of networking that builds up local talent,” she says.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated in-person gatherings in 2020, House of Jane has been adapting with the times. Instead of live events, Vonderheide has been producing monthly videos of artists playing original singles around town, and the change hasn’t been all bad, she notes. For one, it has allowed House of Jane to feature artists who might not have an entire 45-minute set of original music, but do have one or two singles to share. She’s also seen an uptick in the number of views her videos are getting as more music lovers “attend” performances online.

“The drawback is that it still costs money, and I’m not making money anymore,” Vonderheide says. “But luckily I had a reserve of funds, and I got a grant from IAC to keep House of Jane going.”

While it’s uncertain what the winter will bring, Davis, Vonderheide, and Nyberg aren’t slowing down in their commitment to the city’s music scene anytime soon. They’re all three members of the recently formed Madison Music Movement, also known as M3, which is amplifying arts culture with strategic planning, funding, and events, Nyberg says.

Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been sponsoring live music lunches outdoors on Fridays and promoting their local fine arts academy for junior and senior high schoolers.

“We are really digging into this as a community so we can get through COVID and be able to rock on,” Nyberg says.

After all, she herself moved from her hometown Nashville to Madison about 30 years ago because of the potential she saw in the city’s arts scene.

“It had to be a really cool place to pull me out of Nashville,” she says. “Madison is just the best-kept secret.”