How Microschools are challenging public education in Indiana

Offering more personalized education and less oversight, some parents in Indiana are turning to microschools – but educational experts question whether this growing trend will provide a lasting solution to public education concerns.

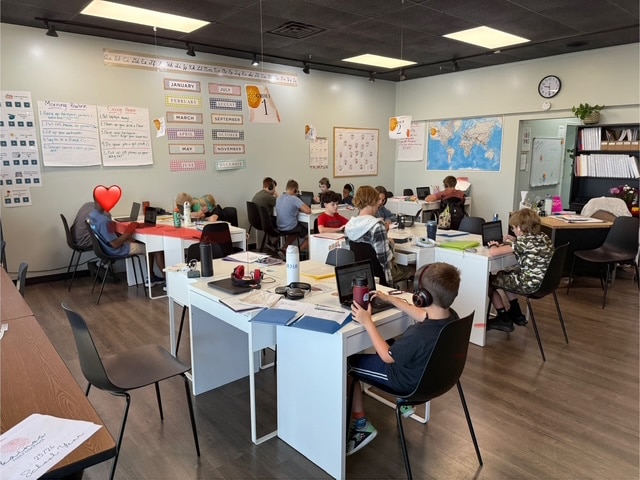

In a commercial strip in central Fort Wayne, you might find a classroom bustling with activity: second graders building nature trails, teenagers tutoring younger students, and a handful of teachers moving from desk to desk, answering questions one-on-one.

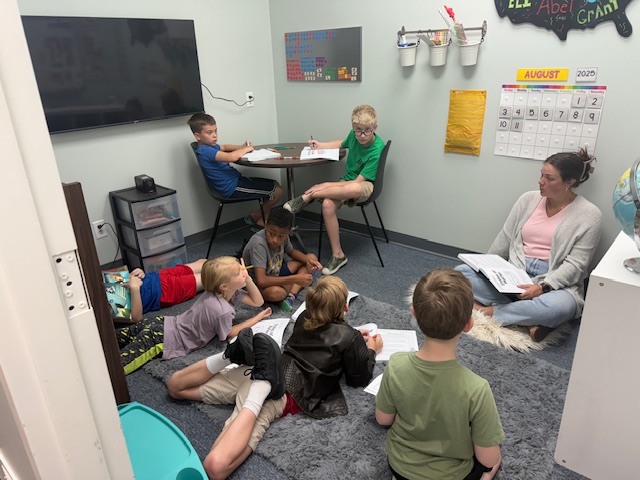

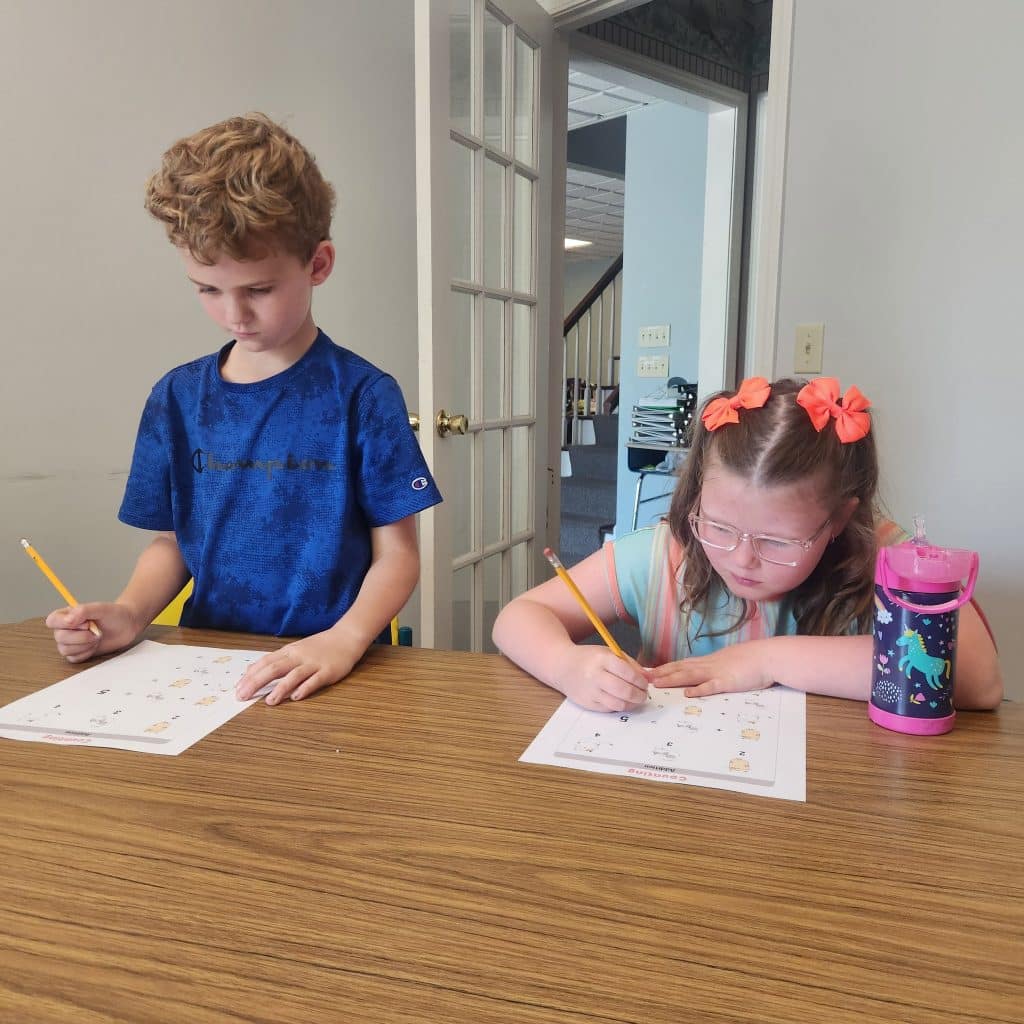

This is Kainos Microschool, one of a fast-growing network of microschools across Indiana. These grassroots institutions are a nod to the one-room schoolhouse days, when a small group of students across multiple grade levels shared a classroom. An alternative to public schools, these learning communities often offer more personalized instruction, including one-on-one and small-group sessions. Microschools can be public, private, or charter schools, depending on the regulatory frameworks in the home state. Here in Indiana, they can fall under these categories, though many are privately run.

Kainos is a faith-based school with a focus on students in grades 2-12 who require a personalized education.

“We’re seeing families that just need something different — kids who were lost in big classrooms, or who learn differently, or families who want more say in their children’s education,” says Jill Haskins, founder of Kainos Microschool.

Fellow microschool founder Leena Edgar, who runs Growing Roots Microschool, describes a similar story: “Families come to us because their kids weren’t thriving in traditional settings. For some, it’s about academic fit, and for others, it’s about wanting a nature-based or more flexible approach.”

As Indiana’s educational landscape changes, microschools are becoming an increasingly visible response to underfunded public institutions. According to the Education Data Initiative, Indiana spends below the national average per student when it comes to public education. The state also ranks 38th in K-12 school spending and funding.

These realities have prompted some parents to think outside the traditional infrastructure when it comes to education. To that end, Haskins estimates there are as many as 30 microschools in the Fort Wayne area alone. She attributes the growth to the fact that some families have found that traditional public schools haven’t kept up with their children’s needs. The downstream effects of underfunding include overcrowded classes and less attention. Not to mention, rigid curricula and limited flexibility frustrate some parents, she says. Haskins believes all of this contributes to the fact that her school currently has a waiting list of 15. It also helps that private schools that reflect the microschool model allow parents to use Indiana’s School Choice Scholarship voucher toward tuition.

Educational researcher and Professor of Education Policy at Indiana University Dr. Christopher Lubienski notes that “reforms” like microschools are part of a larger pattern across the state and country.

“We’ve seen declining trust in public institutions, including schools,” he says. “Indiana’s policymakers have responded with increased support for educational choice and alternative models like microschools. There’s a demand for more localized, personal learning, especially in rural areas where consolidation has cut local options.”

He points out that microschools in Indiana are highly diverse, ranging from faith-based programs like Kainos to secular, nature-focused groups like Growing Roots. What unites them is small scale, customization, and grassroots leadership.

Haskins, who runs the Indiana Microschool Network, agrees that Kainos is the product of these converging factors.

“I started Kainos in my living room last January,” she explains. “I had five kids, and then eight, and then 11. Within a year, we’d outgrown my house and moved into a commercial space. Now we have 21 full-time students and a waiting list. Families are looking for something new.”

Growing Roots, located in a church west of Fort Wayne, offers a nature-based curriculum that blends literature, the arts, and outdoor exploration.

“We’re not sitting at desks all day,” says Edgar. “Our students help make the trails outside, read together in small groups, and draw what they’re learning. For many, this is the first time they’re really excited to come to school. I’ve had parents tear up, telling me their child finally wants to go to school each day.”

The settings are often unconventional. Think converted vape shops, church facilities, former living rooms, with student populations that can range from kindergarten to high school and everything in between. Staff may be certified teachers, retired professionals, or veteran homeschool parents. Teachers at microschools in Indiana are not explicitly required to be licensed, as many operate as private schools or homeschool co-ops. Indiana law does not mandate a teaching license for all private school teachers.

“About 60% of founders nationally are former educators,” says Haskins, “but anyone who’s willing to juggle teaching, business management, and administration can step up.”

Licensed or not, she says the onus lies on the parents to ensure that the quality and level of education is sufficient.

As Haswkins notes, most microschools do not have to report anything to the state per se. They can apply for a school number, but most don’t. They are not required to report attendance, grades, or any other data.

However, Edgar notes that what’s reported to the state depends on accreditation. In her words, “Like all private schools in Indiana, an unaccredited microschool reports nothing and only has to be prepared to submit attendance if asked, which is the same requirement as homeschools.”

It’s this flexibility and the freedom from traditional bureaucracy that leaders say helps them meet children where they are. Each child works at their own pace, Haskins says. Some breeze through math, while others take two years for pre-algebra. In her estimation, what matters is mastery, not keeping up with a rigid timeline.

While large-scale data is still limited, Edgar says they focus on other factors to define success.

“Attendance is a big success indicator for us,” says Edgar. “We rarely see truancy; kids are engaged and don’t want to miss out.”

On a policy level, Lubienski posits that Indiana is a leader in the microschool trend in the Midwest, due to both state funding initiatives and a robust culture of school choice. Indiana is one of the leading states for this movement, alongside places like Florida and Arizona, he says. Further contributing to this climate, policymakers here have provided the frameworks — and sometimes funding — to help these schools start and grow. For example, he says, microschools in Indiana can access public funds as charter schools, through districts, the Choice Scholarship program, or the Educational Savings Account (ESA) program.

Microschools are not a silver bullet, and Haskins is candid about the obstacles.

“Starting a micro school is starting a small business,” she says. “Location is hard. Funding is hard — tuition only goes so far. We’re constantly trying to make it sustainable while staying accessible.”

With those goals in mind, Kainos is working through the state’s accreditation process and exploring scholarship programs. But as she notes, public funds like Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) only reach some students, primarily those with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

Edgar agrees, noting that affordability is always top of mind. Vouchers help, but not everyone qualifies, or the funding isn’t enough. In her words, “We try to balance growing with not losing the small-community feel that makes microschools so powerful.”

From an education policy expert’s perspective, Lubienski sees both practical and systemic challenges.

“A key concern is ensuring quality and oversight, especially as more schools open,” he says. “Accreditation matters for families planning on higher education, and staff expertise can be inconsistent. There’s also the potential impact on public schools. If enough families leave, funding and involvement in public districts could suffer.”

He warns that while individualized models suit some students, they may lack extracurriculars, broad peer networks, or specialized services.

For Lubienski, microschools are both a sign of discontent and of homegrown innovation.

“This movement isn’t likely to disappear, but we should temper enthusiasm with caution,” he says. “Over time, some microschools may ‘revert to the mean,’ becoming more like traditional schools as they grow. Still, this experimentation can reveal what families value — and where the system falls short.”