The history & future of Black farming in Indiana: Leaders meet to address systemic racial barriers

"When things are better for Black farmers, they're better for white farmers, and they're better for communities."

When you think about milestones in Black History, farms in Indiana might not immediately come to mind. But for centuries—even prior to the Civil War—Black-owned farms have played a key role in how Black Americans have forged their own identities, independence, wealth, health, and wellbeing amidst systems designed to repress them. What’s more, one of the nation’s last-remaining 1800s Black farming communities still operates in Indiana, of all places.

About 35 miles North of the Kentucky border, an unincorporated burg called Lyles Station was established in the mid-1800s by free Black residents who worked their own soil—one of dozens of such communities that once existed across what was formerly known as the Northwest Territory.

But the reason Lyles Station is one of the last-remaining communities and the reason you might not associate farming with Black culture in the U.S. is largely one and the same. Since 1920, the number of Black farmers has decreased drastically, from about 1 million to just under 45,000 in 2012.

Since 1910, Black farmers have lost about 90 percent of the total land they once owned, too.

While Nixon-era legislation and the rise of Big Ag have reduced the number of small family farms among all races in the U.S., Black farmers have faced additional barriers to accessing support, information, and financial assistance—challenges that persist into the pandemic and Biden-era. Now, Black farmers across the Midwest, from Lyles Station to Chicago and Fort Wayne, are banding together to build bridges between BIPOC growers and support organizations and to strategize solutions for a more equitable future.

“We’re trying to bring awareness that there are BIPOC farmers here in Indiana, and help organizations get in contact with them,” says John Jamerson.

Jamerson lives in Lyles Station today with his wife, Denise, and their son DeAnthony. In 2017, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture opened an exhibit about Lyles Station, which featured Denise’s father, Norman Greer.

Jamerson and his family continue to honor this heritage by running the organization, Legacy Taste of The Garden today. It’s a family farm designed to pass on generational knowledge of sustainable and entrepreneurial living through farming and gardening, practicing the same “enterprising and frugal” tactics that helped Lyles Station survive.

Two of the Jamersons’ own projects, the Legacy Farming and Health Group and the new Indiana Black Loam Conference, speak to this spirit of innovation against all odds. Within their advocacy group and statewide conference, they are bringing BIPOC growers together across the nation to share best practices, to develop win-win collaborations, and to address systemic barriers to funding, land ownership, food access, and more.

It was through these efforts Jamerson connected with a like-minded organization based in Fort Wayne, known as the Human Agriculture Co-operative, run by Ty Simmons. The two met about four years ago at a meeting of the National Black Farmers Association. Since then, they’ve been collaborating on multiple projects to expand support for oppressed growers.

“Within our network, what we’ve been working on is basically economic equity and sustainability,” Simmons says. “We’ve been working on barriers in every aspect of African American history in America, be it land and business ownership, inequities in education, professional careers, and definitely in farming. We’re working with Legacy Taste of the Garden, USDA, and NRCS—basically all the farming acronyms—to break the barriers in having access to information, access to applications, access to grants, access to mentorships. What we’ve seen, unfortunately, is that systemic racism has created systemic barriers.”

In some ways, the COVID-19 pandemic has reinvigorated state and national conversations around food access, equity, and racial justice—key topics that have risen to the surface of public consciousness since 2020.

In Fort Wayne, Simmons has been part of several local efforts to grow and deliver food to food deserts in the city, where many People of Color live. Through his partnership with the Jamersons and other BIPOC farmers, he and his team have received grants from the CARES Act and Partnership for a Healthier America, which have allowed them to deliver boxes of fresh produce to residents in need in Southeast Fort Wayne, as well as other in six other states where their partners work, from Gary, IN, to Chicago, IL, and St. Louis, MO.

Together, these groups have delivered more than 3 million pounds of food to residents in need, on top of more than 10,000 free meals Simmons and his local collaborators have distributed on Oxford Street through their regular curbside BBQ pickups.

“John and I continue to grow food and to mentor young people throughout the state,” Simmons says. “We’re working toward scaling these efforts in Fort Wayne by acquiring more land and more partners.”

Despite this progress, state and federal support for Black farmers remains limited overall, Jamerson notes. Even in instances where federal dollars have been earmarked for BIPOC farmers, only a fraction of that funding actually trickles down to the growers themselves and to Black farmers specifically, continuing a trend of financial barriers that have been holding back Black growers for centuries.

Most recently, Biden’s stimulus relief package made headlines in March 2021 as the “most significant legislation for Black farmers since the Civil Rights Act.” It promised about half of its $10.4 billion American Rescue Plan to support agriculture would go to BIPOC farmers broadly as restitution for decades of discriminatory lending practices by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and other groups. However, by December, white farmers blocked the program in court, calling its race criteria unconstitutional. As a result, the funding was broadened into the Build Back Better Act (BBBA), which supports farmers based on economic security rather than race, weakening its ability to compensate for generational losses and challenges endured by Black, specifically.

Jamerson points out that only about 25 percent of BIPOC farmers are Black, and there was nothing to ensure the money would support them. Even under the initial plan, only about 2 percent was likely to reach them, and roughly $5 billion that was supposedly allocated for BIPOC farmers is still only a fraction of the $1.9 trillion relief bill.

“America doesn’t grow enough food to feed itself,” Jamerson says. “Why was what went to BIPOC farmers the only thing halted?”

Jamerson confirms that many times he’s inquired about grants that are supposed to help Black farmers in Indiana, he’s met with dismissive responses.

“We’ve reached out to individuals across the state who have been known to get these grants that are supposed to help BIPOC farmers and said, ‘Hey, we have groups of BIPOC farmers that will want to partner with you.’ They tell us, ‘There’s no room for you,'” Jamerson says.

Simmons adds: “These funds are being filtered to a lot of the huge non-for-profit organizations that have big administrative fees, and once it gets down to where it needs to be—to the Black farmers—there’s nothing left. The trickle-down approach isn’t working. We need funding that goes directly to the people—to the farmers—and trickles up instead.”

“What we’re seeing right now is the illusion of inclusion,” Jamerson says.

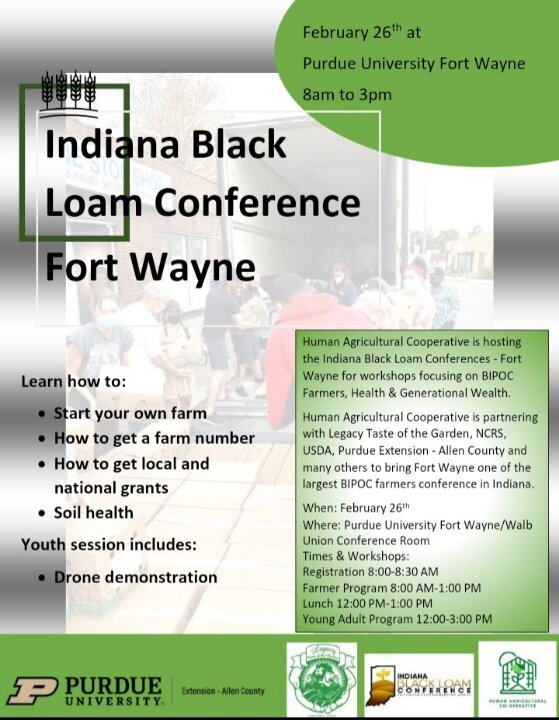

To raise awareness about these challenges and to create a stronger, more unified presence for Black farmers in collaborating with national organizations, like the USDA, Legacy Taste of the Garden is hosting its first Indiana Black Loam Conference this Spring. The conference includes workshops across the state in Evansville (2/19), Fort Wayne (2/26), Gary (3/12), and Bloomington (3/19), followed by a convention-style event in Indianapolis this Spring.

“These events focus on the needs of the underserved Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) farmers, producers, and communities,” a press release says.

Jamerson believes the conference will help Black and BIPOC farmers share their knowledge and receive recognition for their strides so far. It will also provide a direct point of contact between a mass of BIPOC growers in Indiana and national organizations purporting to help them, creating a richer soil, you might say, for these growers to thrive.

“Those who are in agriculture know that loam is the best, richest, most productive soil you can get,” Jamerson says. “That’s why we named our conference Indiana Black Loam. We want to create an environment where attendees have the best or richest opportunities to be able to grow. Sometimes, when you find out that the game is too rigged, it’s time to change the game. That’s what we’re here to do; we’re here to create opportunities for our people.”

By hosting workshops in multiple cities, the goal is to strengthen connections between Black farmers and local groups with resources to help them, so that knowledge at a centralized state convention doesn’t get lost in translation when leaders return to their communities. Each city’s workshop will give BIPOC growers in that area the chance to contextualize the unique challenges and opportunities within their region, too.

“We don’t want to come into a community and tell them, ‘This is what you need to do in your community,'” Jamerson says. “We’re going to provide them with the individuals who can help them with what they need, like being better equipped to apply for loans and things of that nature. But we’re allowing them to have that say in their own household, so to speak.”

Simmons says the workshop in Fort Wayne will have activities for adults and children alike, providing a chance for anyone interested in learning about farming, gardening, and its multitude of benefits to join the conversation. It is open to people of all races, ages, and backgrounds. After all, food is a pervasive topic, which he has found engages residents in a variety of beneficial ways.

“We’re asking city leaders and white farmers to collaborate with us because it’s going to take more than just Black farmers to improve conditions,” Simmons says.

Through his own programs with the Human Agriculture Co-Operative, which have served more than 100 youth of all races in Fort Wayne the past seven years, he’s seen youth apply skills they’ve gained farming and gardening to many aspects of their lives and careers.

“It’s not just a farming program; it’s a lifestyle program,” Simmons says. “We use farming and gardening to teach young people about life. While we’ve had one or two go into the agriculture field, many have applied the skills they’ve learned to go to college and into the tech industry or into the trades as barbers. In many ways, it’s about building young people who understand the systems they’re born into, but also understand how to achieve and to go beyond.”

Looking to the future, Simmons hopes to continue fostering understanding and momentum around Indiana’s food systems, equity, and the state of farming here. After all, the fact that Indiana’s farm scene has largely consolidated into the hands of a few Big Ag corporations is an issue that hurts farmers and consumers across all races. He hopes to keep pushing back against this trend, bringing farms and gardens back into communities that desperately need access to the health and economic benefits local food provides.

“We want to make conditions better, not only for Black farmers and Black communities, but for cities,” Simmons says. “When things are better for Black farmers, they’re better for white farmers, and they’re better for communities.”

Learn more

Fort Wayne’s Indiana Black Loam workshop will be held Feb. 26, 2022, from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at Purdue Fort Wayne. To learn more and register, visit https://bit.ly/black-loam-events.