When legislators become learners: Bridging the gap between policy and early childhood education

Early childhood education advocates are inviting legislators into classrooms in hopes of addressing systemic issues in childcare across Indiana.

When state legislators visit a site, it’s often a ribbon-cutting or a roundtable with adults in suits. But when one stepped into Lutheran Social Services of Indiana’s Children’s Village this fall, they found something different: toddlers finger-painting, teachers guiding tiny hands through colors and shapes, and children learning through play.

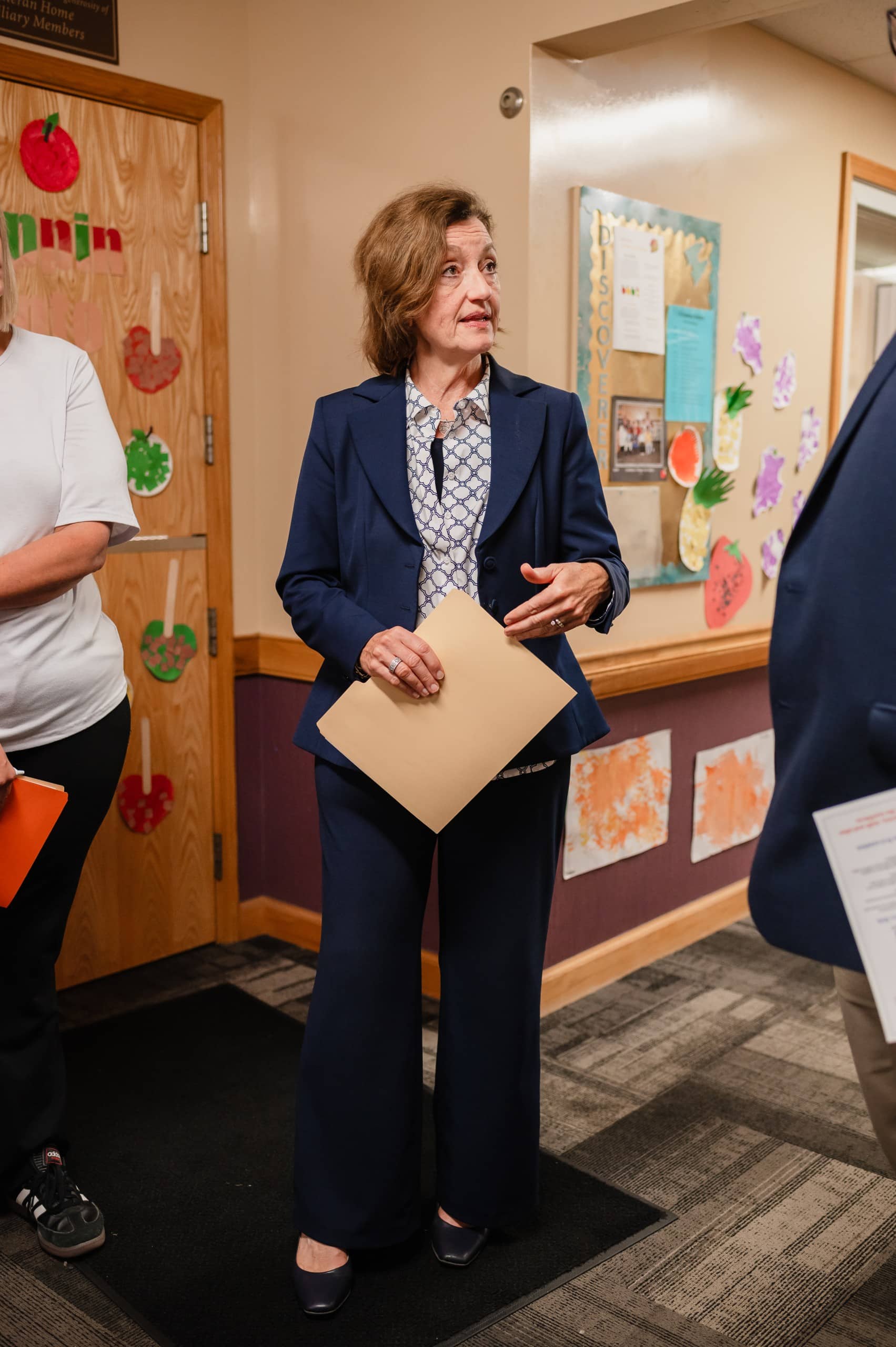

For Angela Moellering, president and CEO of Lutheran Social Services of Indiana (LSSI), that moment captured everything her staff had been trying to communicate for months: early learning isn’t just a line item in the budget. It’s real, it’s local, and it’s struggling.

A system under strain

Indiana’s childcare system has a history of running on thin margins. For decades, the state ranked near the bottom nationally in early childhood investment, with most funding tied to the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), a voucher program that helps low-income families pay for care.

In 2014, Indiana launched On My Way Pre-K, its first publicly funded preschool for eligible four-year-olds. The pilot showed strong results but remained small in scale, leaving most centers dependent on private tuition and philanthropy to make up for low reimbursement rates. That patchwork model forced providers to make tough choices: raise tuition, cut teacher pay, or absorb losses themselves. Many early educators, earning just $12–$14 an hour, left the field entirely, creating what advocates now call “childcare deserts.”

In recent years, groups like the Northeast Indiana Early Childhood Coalition were warning that the system was becoming unsustainable, calling childcare a “vital infrastructure that supports our workforce and economy.”

The pandemic briefly stabilized things, as federal relief funds poured in to keep centers open. But those dollars didn’t fix the system — they only held it together.

When that funding began to expire in late 2023 and was fully phased out by September 2024, the same cracks reappeared. Then, as relief money dwindled, the state’s Family and Social Services Administration slowed spending to save money, halting new CCDF enrollments and leaving thousands of families on waiting lists. The move sparked protests at the Statehouse, as providers warned that many centers were on the brink of closing.

Allie Sutherland, executive director of the Northeast Indiana Early Childhood Coalition, notes that in Allen County, a Level 4, high-quality childcare center costs about $468 a week for an infant, while many teachers earn less than $15 an hour. Even families earning around $60,000 a year — well above the poverty line — are priced out.

“A family of four at that income is spending between $10,000 and $20,000 a year on childcare,” Sutherland notes. “It’s an impossible equation.”

Moellering says her organization has felt those effects acutely. “We’ve gone from having sixteen infants at our center to having one,” she says.

Her center serves mostly low-income families, with 91 percent relying on CCDF vouchers. Since Indiana stopped issuing new vouchers in November 2024, many of those families have been left without affordable options.

“When funding is cut, families lose access to safe, high-quality care,” Moellering says. “And that affects our entire community.”

“Childcare isn’t just a family issue,” Sutherland adds. “It’s economic infrastructure. Without it, our entire workforce suffers.”

Building bridges between the Statehouse and classrooms

In early 2025, as providers faced mounting financial pressure, Sutherland and her colleagues decided to take action. They launched Legislators and Learners, a statewide effort under the Hoosier Milestones coalition designed to connect policymakers directly with early childhood programs.

“We realized that so many of these policy discussions were happening without the people who actually run childcare programs,” Sutherland says. “Every county was trying to solve the same issues separately, without a unified voice. Legislators and Learners is about creating alignment and getting everyone to the same table.”

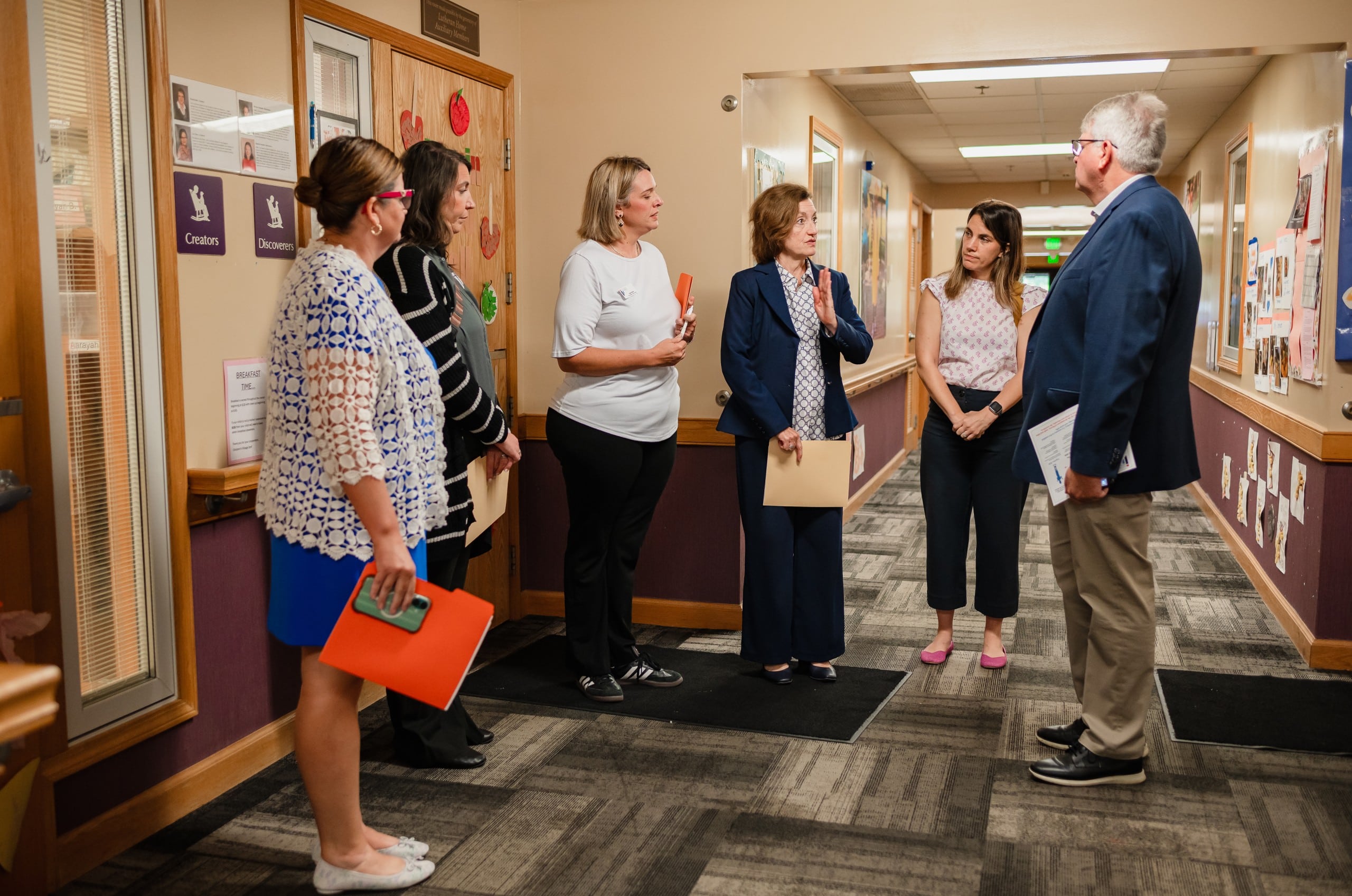

Through the initiative, childcare providers host lawmakers for informal visits where they can see early learning in action and hear directly from educators and parents.

“It’s about humanizing the issue,” Sutherland explains. “When you meet the teachers and families behind the statistics, it changes how you see the problem.”

In Northeast Indiana, several lawmakers took time this fall to visit early learning centers in their own districts, including Rep. Dave Abbott (R–18), Rep. Kyle Miller (D–82), Rep. Phil GiaQuinta (D–80), Sen. Justin Busch (R–16) and Sen. Travis Holdman (R–19).

For Sutherland, those visits represented exactly what the coalition hoped to achieve: connection between legislators and the families they serve.

“We’re making sure we invite them to a center in their constituency,” she says. “Your constituents are using this. This is how it’s impacting the people you represent.”

Moments of understanding

During one visit, a legislator posed a question that stuck with Moellering: What would it take to rebuild if funding returned tomorrow?

She appreciates the thought behind it, because it acknowledged something many overlook: restoring funds isn’t the same as restoring capacity. As she explains later, even if the state resumed voucher funding overnight, the recovery would take time.

“I appreciated that there were questions about, okay, so we return everything back tomorrow to the way that it was,” she says. “What are the challenges for raising back up? Because there are some significant things that would have to happen.”

Many of her teachers had already left for other jobs, she explains, and rebuilding a team would mean months of hiring, onboarding, and training.

“It’s not just an immediate problem we can fix by turning a light switch back on,” she noted. “It’s going to take us a while to get back to where we were.”

Those candid exchanges, Moellering says, matter.

“It was encouraging to see genuine interest,” she reflected. “The questions were thoughtful, and there was acknowledgment that this is complex.”

A lawmaker’s perspective

Rep. Phil GiaQuinta, the House Minority Leader from Fort Wayne, was eager to see firsthand how early learning classrooms operate.

“Legislators get invited to all kinds of events to observe how things work,” he says. “But with everything that’s been happening around childcare vouchers, I wanted to see firsthand what that means in the classroom.”

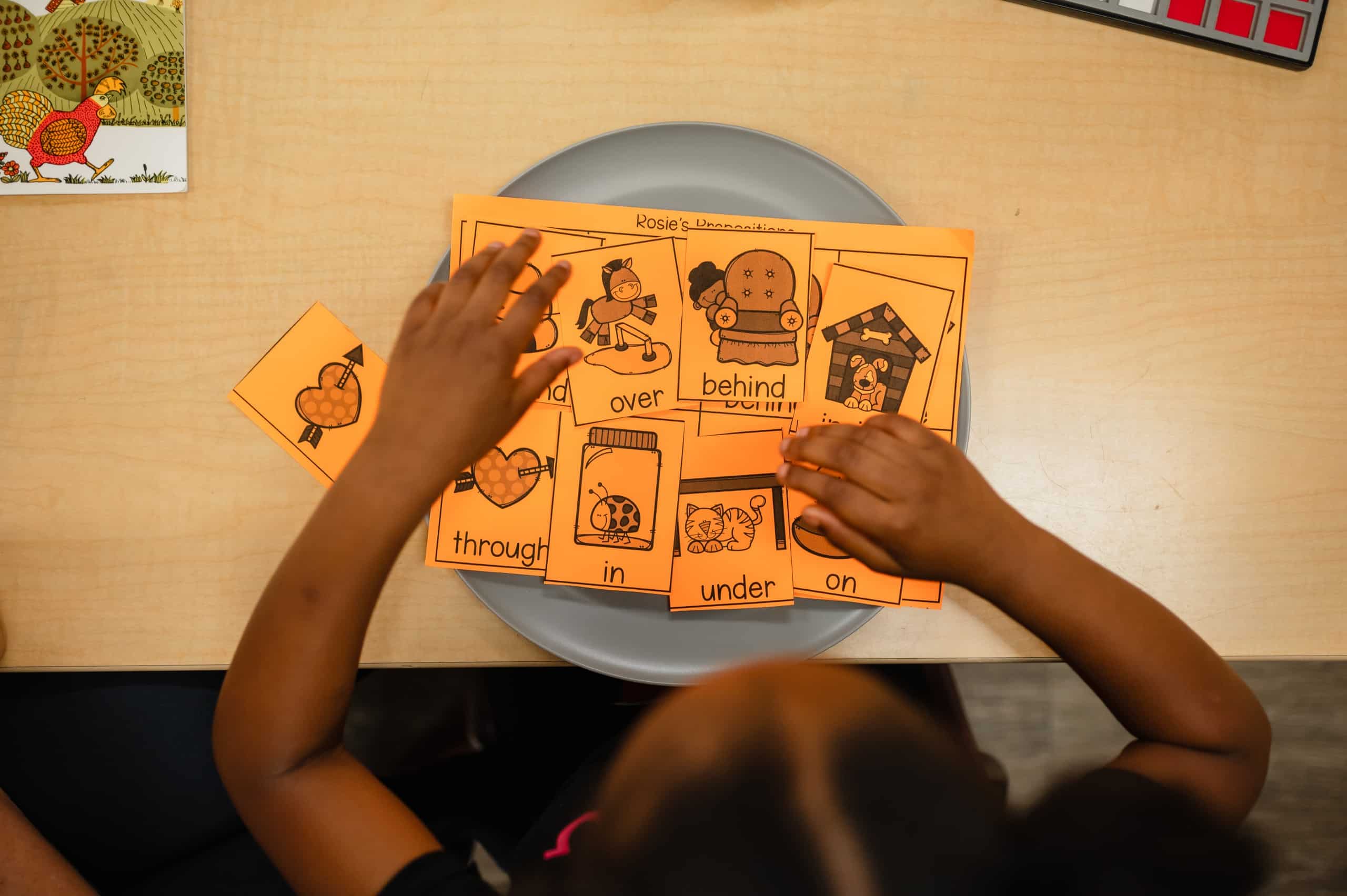

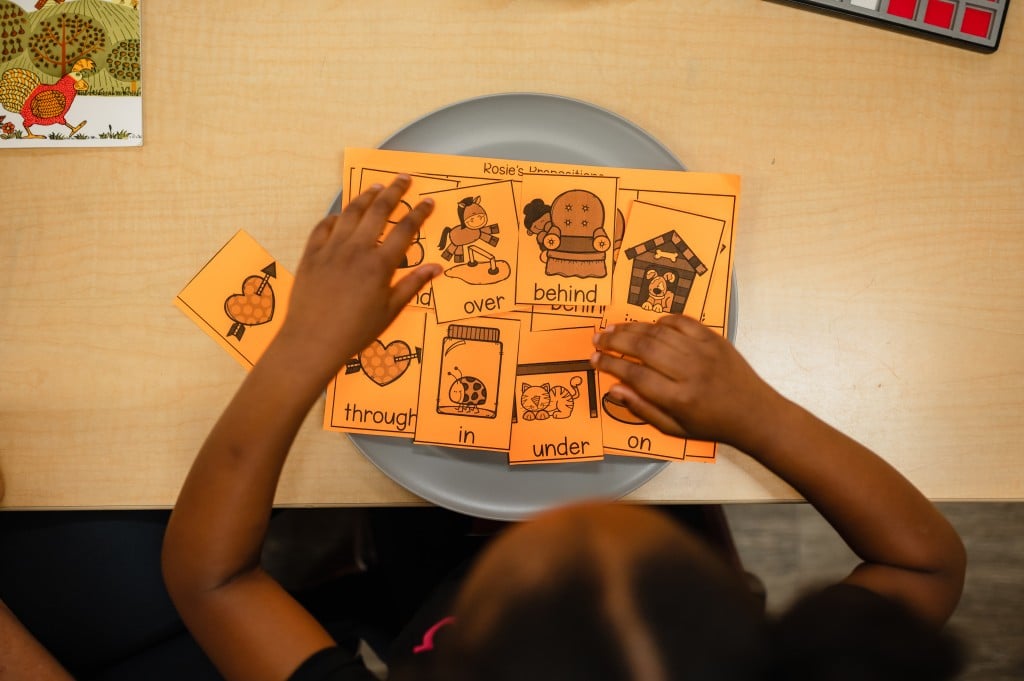

Inside Children’s Village, GiaQuinta was struck by how engaged the children were and how intentional the teaching felt.

“The teacher I observed was using visuals, like a suitcase activity, to teach new words and ideas,” he recalls. “The kids were totally locked in. You could tell how much learning was happening, and how much it mattered.”

The visit reaffirmed for him how central early education is to the state’s long-term priorities.

“The data is clear: kids who go through pre-K programs perform better in third-grade reading and beyond,” he says. “The investments we make early on pay off so much more down the road than doing nothing at all.”

Still, what resonated with him wasn’t only the numbers on a page but also the people behind them, whose commitment gave the data meaning.

“You could tell they really care about what they’re doing,” he says of the teachers. “You can see it in how they talk about the kids… It’s clear this means something to them.”

A rare bipartisan effort

In an era of deep political division, childcare has proven to be one of the few issues capable of bringing lawmakers together. Republican and Democratic lawmakers alike have been visiting centers, listening to providers, and asking detailed questions about what it takes to keep classrooms running.

Sutherland says the mix of participation has been encouraging. “I think it’s very much a bipartisan issue,” she says.

GiaQuinta agrees. “It’s both an education issue and a workforce issue,” he says. “When we talk about helping people get back to work or filling job openings, you can’t separate that from child care. It’s something I think both parties and business leaders are starting to understand more.”

And that understanding, advocates say, is key to progress. Business coalitions and chambers of commerce across Indiana have begun emphasizing the same message: that accessible, high-quality childcare is essential to economic growth. The more legislators see that alignment, the easier it becomes to find common ground.

Innovation amid uncertainty

While the future of state-level funding remains uncertain, local advocates are pursuing creative solutions to keep childcare accessible. One promising model is Tri-Share Plus, a cost-sharing initiative in Northeast Indiana that splits childcare expenses among employers, families, and the state.

So far, 11 employers have joined the pilot, with several more in the pipeline. While the program is no silver bullet for Indiana’s childcare challenges, Sutherland says it’s showing promising results and making a difference.

“Employers who are participating are seeing employees stay longer and show up more reliably, and families finally have a little breathing room. Providers are also getting paid closer to what their care actually costs,” Sutherland says.

However, she’s quick to note that programs like Tri-Share can’t replace the state’s role. “We can’t expect employers or philanthropy to solve a systemic problem,” she says. “Those kinds of programs can fill in the gaps, but we still need consistent, sustainable funding from the state if we want this to last.”

After a year of funding freezes and closures, both Sutherland and Moellering say the Legislators and Learners initiative has offered a small but genuine sense of encouragement that their message is finally being heard.

“At first, we weren’t sure anyone would show up,” Sutherland says with a laugh. “Now we’ve had fifteen visits and counting. That tells us people care, and that’s a start.”

Moellering shares that feeling. “This isn’t just about our center,” she says. “It’s about children who deserve safe, nurturing care and parents who deserve to be able to work without worrying how they’re going to pay for it.”

For both, the visits feel like the beginning of a longer conversation. “It’s not going to happen overnight,” Sutherland says. “But every visit, every conversation, it all helps move things forward.”

She adds that seeing lawmakers on the floor with children often makes the issue real in a way data alone cannot. “It’s different when a legislator sits on the floor with the kids. You can see it click,” she says. “That’s where the change starts.”