Addressing the housing crisis in America’s most affordable city

"We can undo the effects of suburbanization in the Midwest, and we can do it in a way that’s good for everyone."

It’s 85 degrees, and two o’clock in the afternoon on Holton Avenue, about 10 minutes southeast of downtown Fort Wayne.

Three children, no more than eight years old, are running around the yard in their bathing suits, laughing as an adult chases them with a hose.

There’s a summer camp going on today, and the children are taking a break in the yard between the old St. Hyacinth Church and the white Vincent Village House next door.

Denise Andorfer, Executive Director of the nonprofit, is sitting on the steps of the house when I arrive. She’s managed the organization for about six years, and she’s waiting on me today for an interview about the lack of affordable housing in Fort Wayne.

Since the dawn of viral internet lists, Fort Wayne has been rated one of the “most affordable” places to live in the U.S.

Most recently, Niche said it has the lowest cost of living in the nation based on the consumer price index and access to affordable housing. But that’s where things get confusing.

There’s no hard and fast rate that determines what’s “affordable” to people.

So “affordable housing” is a generalized term that really only speaks to a portion of renters and homeowners who fall into a sweet spot of median area income where they live.

For others in poverty or rising out of it in Fort Wayne, there’s a different side of the story.

Instead of “the most affordable place to live,” they see Fort Wayne as the place where they can’t find a home to use their housing voucher, or worse—the place with the 13th highest eviction rate in the nation.

“I’ve lived in Orlando, and I’ve lived in northern Virginia, and I look at Fort Wayne as being different than that,” Andorfer says. “But every day in this city, we have eight people who are being evicted.”

These statistics were made common knowledge earlier this year thanks to Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond who established the nationwide database Eviction Lab.

Desmond published a Pulitzer Prize-winning book called Evicted in March 2016, chronicling the housing crisis through the lives of eight families in the poorest neighborhoods of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The Eviction Lab at Princeton University takes his work a step further by creating the first database of evictions to localize the crisis in cities across the country.

Using the website, citizens can create custom maps, charts, and reports about evictions in their area.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) classifies families as cost burdened if they are spending more than 30 percent of their annual income on housing. Even so, it estimates that 12 million Americans are spending more than half of their annual income on housing alone.

“A family with one full-time worker earning the minimum wage cannot afford the local fair-market rent for a two-bedroom apartment anywhere in the United States,” the website says.

And housing issues don’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

As former Rust Belt cities like Fort Wayne redevelop their urban cores, cost burdened residents who filled these areas during economic downcycles are likely to be displaced.

But in this time of crisis, there is also a chance to rebuild something greater than what currently exists, and that’s what gives Andorfer hope.

There is an opportunity to build a stronger, more inclusive community structure—one family, one stable home, one story at a time.

***

Vincent Village is considered a transitional shelter for a population known as the “working poor,” Andorfer says.

“We’re letting the Rescue Mission focus on the guys in the tents downtown, and we’re working with the single moms making $8 an hour,” she says. “It’s the people who say, ‘I’m working, and I still can’t afford my basic needs.’”

In the late 1980s, the Catholic Diocese donated the old St. Hyacinth convent as the Vincent House to be a small refuge for homeless families in Fort Wayne.

Over the years, the Diocese has donated more property and the organization has raised funds to create an entire village—a close-knit community with an ever-increasing number of houses where families move out to once they get on their feet.

Residents begin Vincent Village’s program in one of the shelter’s 10 rooms for $150 a month. They can stay there for up to two years, working with the organization’s leaders and volunteers to build a sustainable life.

Then they have the opportunity to rent one of the shelter’s 35 houses down the street and around the block for up to five years.

At the houses, residents pay up to $550 a month in rent, Andorfer says. The idea is to help them acclimate to independent life to avoid eviction and homelessness in the future.

But what residents often find is that when their time at Vincent Village is up, the life they’ve prepared for—the life between a shelter and a stable home to rent or buy—is limited in its options.

Andorfer introduces me to the woman sitting next to her on the steps, one of Vincent Village’s residents, Antoinette, who happens to be waiting on some paperwork today.

She came to Vincent Village about five years ago with her son and worked her way up from a single room to a house down the street.

This year, her son is graduating from high school, so she doesn’t qualify for family housing anymore. On top of that, her time at Vincent Village is up to make way for new residents—more than 40 on the waiting list.

Now she needs a safe, affordable place to live in Fort Wayne on her own, but everything is either full or doesn’t accept Section 8.

“She has a housing voucher, but there aren’t enough places for people to use their housing vouchers,” Andorfer explains.

So where is Antoinette supposed to go?

***

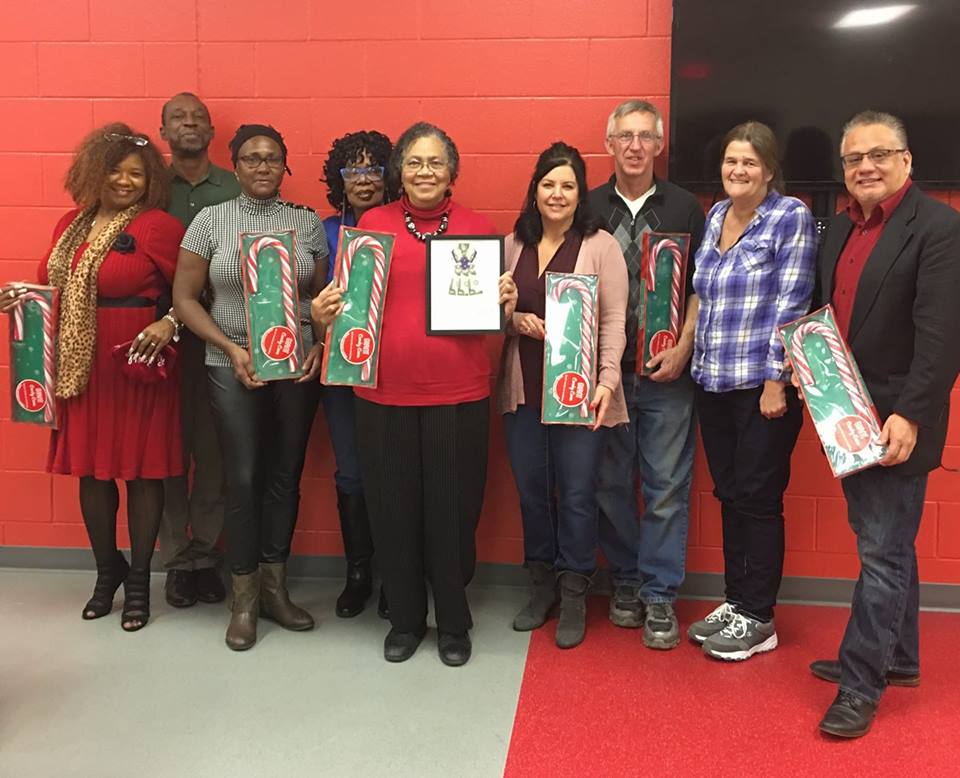

Heather Presley-Cowen worked in the City’s Office of Housing and Neighborhood Services for about 25 years.

During that time, she noticed the same problem Antoinette is experiencing in Fort Wayne’s housing system.

“One of the things we saw that was our entire housing system is clogged,” Cowen says.

Eight people in Fort Wayne are being evicted today. Eight more will be evicted tomorrow. And the day after that into the foreseeable future.

Families in emergency shelters already can’t move into transitional housing at places like Vincent Village because there isn’t enough space. Then when they do get in, they can’t find housing when they get out.

“Even though we’re one of the most affordable cities in the nation, we don’t have enough housing that’s affordable to families earning below the median area income,” Cowen says.

But Fort Wayne isn’t the only city in northeast Indiana with housing issues.

That was another thing she noticed while working for the City. She saw that several regional governments didn’t even have someone in her position to focus on housing fulltime.

So in 2016, she decided to start her own firm called Capacity Enhancement & Development Services (CED) Services LLC to take on northeast Indiana’s housing challenges from a regional perspective.

“I just look to help fill gaps,” Cowen says.

Seeing her interest in the issue, friends encouraged her to meet Andorfer at Vincent Village, and when she did, she was impressed.

“I started to volunteer with her because I believe in her model,” Cowen says.

But while she sees the nonprofit’s model as perhaps the most effective way to address housing issues in Fort Wayne, she says it might also be the most difficult to replicate.

“What’s difficult to replicate is that, just like every human being has a different set of issues, this problem is multifaceted,” Cowen says. “Denise and her team are focused on not just providing housing, but also on coming alongside of that family and working through a whole host of issues that come along with remaining housed.”

The same personalized approach that makes Vincent Village’s model effective is also what makes it rare.

***

When Andorfer started working at Vincent Village in November 2012, the organization was receiving its annual funding from $30,000 in state grants, and three HUD grants totaling $180,000.

Then about three years ago, HUD developed a new approach to the housing crisis called Housing First.

Rather than requiring homeless families to participate in and graduate from programs before they qualify for permanent housing, the Housing First model puts them into housing without conditions to entry like sobriety, treatment, or service participation.

Andorfer says Vincent Village doesn’t believe in this approach.

“The answer isn’t just a house,” she says.

Instead, the organization continues to work with families every step of the way to help them build better lives—from offering camps for their children, to teaching classes about home maintenance, to providing opportunites for them to grow their skills or find stable employment.

After all, that’s how evictions tend to happen, Andorfer says.

Families acquire homes they aren’t able to maintain, or the income-earner loses a job, and then the house is gone.

So instead of putting housing first, Vincent Village puts people first, and while it has cost them thousands in HUD funding, it has freed them to better serve homeless families in other ways.

“The only government funding we receive is to help us build and maintain the houses,” Andorfer says. “So we don’t have a government contract where we have to do what the government tells us.”

This allows them to focus on families’ individual needs and do what works, Andorfer says.

Vincent Village actually owns two 501c3 nonprofits: One is a service provider, and the other is a community housing redevelopment corporation, so it can get funds from the city to rehab houses.

Today, its $1.2 million annual budget is all from private donations, individuals, and corporations—not to mention 1,400 people who have volunteered their time with the organization in the last year.

On average, Vincent Village serves 45-50 families a year, its website says.

“We’re not about playing a numbers game,” Andorfer explains. “We don’t want to put a Band-Aid on a thousand people. We’d rather change the lives permanently of 300 people.”

To accomplish such an involved task, the organization relies heavily on its partnerships throughout the community with organizations like Fort Wayne Community Schools, the Renaissance Point YMCA, Parkview Health, NeighborLink, Catholic Charities, The Chapel, and Park Center.

During the course of one afternoon, neighbors might stop by several times to talk, borrow lawn equipment, attend a class, or find someone to help jump their car.

“We pride ourselves for filling in for all kinds of things,” Andorfer says. “It’s just how we operate.”

And as we speak inside Vincent Village’s Sally Weigand Community Center on Holton Avenue, the door opens again.

***

A black woman in a black and white dress opens the door and looks around frantically.

She’s looking for a meeting about the new affordable housing at Bottle Works Lofts, she says, looking at Andorfer and then back at her driver in a car waiting outside the door.

Just down the street, the Bottle Works development offers 31 apartments in a historically renovated Coca-Cola factory along with 19-single-family homes throughout the Renaissance Pointe neighborhood.

All of the living spaces are income-qualified, and Vincent Village is a co-developer on the project.

But when Andorfer tells the woman that the meeting isn’t tonight, she hangs her head in silence for a moment. Then looks back up at us and walks quickly toward the table where we’re sitting.

“Well, what do you guys do?” She asks Andorfer. “I can’t find a house. I’ve got a voucher, and I can’t find a house.”

“We’re actually doing a story about housing issues in Fort Wayne today,” Andorfer says.

“Oh, come on,” the woman says. She looks at me excitedly and motions “one moment” with her finger.

She turns quickly and to fix her hair in the microwave reflection, adjusts her glasses, straightens her dress. Then she sits down across from me, and points at me with a long fingernail, tapping it on the table between us.

“Let me tell you; let me tell you,” she says.

Then she bursts into tears.

***

“I think this is my first time crying today,” the woman says between sobs. “It’s overwhelming, and I’m just tired. I want to run away.”

Her name is Lisa Wilhite, and she’s 52. She says she was renting a house for six years. Then she lost it when the owner sold it, so she signed up for a housing voucher for Section 8 and received it on March 24th.

Now, it’s near the end of June, and her voucher is about to expire. But she hasn’t found a house, so she has to go back and get it renewed.

She’s dressed up today because she thought she was meeting with someone about housing, and she wanted to present herself well.

“I want them to know that I’m interested—that I’m going to take care of their property, you know,” she says. “That’s how I feel. It’s like it’s a job.”

Instead, what she’s found is that searching for Section 8 housing in Fort Wayne is a job in itself.

“I’ve been lookin, and lookin, and lookin, and lookin,” she says. “Nobody wants to mess with Section 8 because some of the other renters that had it tore up the property. Or either got kicked out the program for doin’ drugs.

“It’s messed things up for people like me,” she says. “I’m telling you guys, I’ve looked at over 100 houses, and a lot of the rental properties don’t even sell Section 8. They don’t want nothing to do with it.”

To offer Section 8 housing, landlords have to go through lengthy inspections, Andorfer says.

“There’s a lot that goes into it,” she explains, reminding us that landlords have a side of the story, too.

After all, they need to make money on their investments and keep the roof over their own heads.

She just wishes she could start a conversation and get everyone around the same table to hear each other’s stories—the landlords, the renters, the city leaders, and the organizations like Vincent Village around town.

In her experience, everyone has a story to tell, and it’s hearing people’s stories that makes the biggest difference.

People in Fort Wayne may assume that housing is something government takes care of—something you can easily find if you look hard enough, Andorfer says.

But for many of the “working poor” in Fort Wayne, that is simply not the case.

“It’s very tough taking the bus to an $8 an hour job, and you just literally can get nowhere,” she says. “People are often demonized for somehow not being hardworking enough. But I once heard someone say: ‘It’s hard to pull yourself up by your bootstraps when you don’t have boots.’”

***

With every challenge, there is an opportunity, and if the challenge is stable, affordable housing, then the opportunity is to build more stable, equitable communities.

That’s how Steve Smith sees it.

Smith is CEO of the Model Group, a Cincinnati-based development firm specializing in urban revitalization, where he has been a thought-leader in the affordable housing industry across the Midwest.

His firm prides itself in building affordable living spaces that are indistinguishable from market-rate housing to weave cities back together with people of many backgrounds and incomes living in close proximity.

One of Model Group’s most notable projects to date is rehabbing the Over the Rhine (OTR) cultural district in inner-city Cincinnati, beginning in 2003.

Today, it is home to neighborhoods like Findlay Market, which is one of the most culturally diverse places in the entire state, Smith notes.

Since the completion of OTR, Model Group has picked up similar projects across the country, including The Landing in downtown Fort Wayne.

But in addition to creating some affordable living spaces there, his firm is also interested in helping Vincent Village rebuild its surrounding Oxford neighborhood in Southeast Fort Wayne.

Andorfer says Model Group has been out for three or four tours of the neighborhood where they have proposed building affordable housing in several vacant lots left by home demolitions.

“The question is: Do you just let those lots sit, or do you put up new houses?” Andorfer asks.

But while there’s an economic incentive for cities to rebuild, there’s more than brick-and-mortar that goes into rebuilding a neighborhood, Smith says. That’s why his firm was interested in partnering with Vincent Village in the first place.

The national housing crisis is not only a matter of supply, but also of demand, he explains.

While the supply side of the equation will always be short to some extent, cities can work to curb the demand for affordable housing by helping residents access sustainable lifestyles.

“One of the things that people are learning nationally is that there’s always a need for more affordable housing. But it’s unlikely that we’re ever going to be able to build our way out of the affordable housing crisis,” Smith says. “What I like about what Vincent Village is doing is that they do things to mitigate the crisis, but also to teach people how to be self-sufficient.”

Even so, Vincent Village’s model of self-sufficiency isn’t focused on self-made independence.

Instead, it relies heavily on the supportive structures of a neighborhood—or a village—to thrive. It’s a community working together to meet each other’s needs regardless of government intervention, Cowen says.

“When you look at the way our neighborhoods were originally built—they were built to actually support people,” she says.

Looking to the future, Vincent Village is tasked with rebuilding neighborhood support structures amidst changing economies, federal funding cutbacks, clogged housing systems, and a host of other issues.

But it’s not just a task for them.

After all, a region’s housing issues are not contained to its renters and its landlords, the people who can’t afford housing, or the governments and organizations trying to provide it.

Instead, these issues affect every resident in some way—whether we realize it or not.

“Housing is a very local issue, yet many communities don’t see housing as an economic driver and as part of a community’s infrastructure,” Cowen says. “Ultimately, it comes down to stronger families make up stronger neighborhoods, and stronger neighborhoods are a good place to be in business.”