Allen County residents rally for rivers

Inside the Save Maumee Grassroots Organization that's preserving northeast Indiana's waterways.

As Riverfront development is underway, there’s much talk about improving the water quality of Fort Wayne’s three rivers.

But doing so involves more than looking at the rivers themselves, says Abigail Frost-King. It also involves taking a look at the three river’s native species, vegetation, and riparian areas or adjacent wetlands.

In 2013, King founded Save Maumee Grassroots Organization after buying a house on the Maumee River and quickly observing the destruction and neglect that is doing irreparable damage to the river and the greater Allen County environment.

“Rivers don’t pollute themselves,” she says. “It’s a combination of different elements that cause the contamination.”

Among those components are disease and the introduction of multiple invasive species that all-too-often compete with native species for water, sunlight, space, and the rich nutrients in the soil.

So as the leader of Save Maumee, she’s in the midst of a gargantuan effort to reforest the drainage areas that flow into the Maumee River, which starts at the confluence of the three rivers in downtown Fort Wayne and flows northwest through East Allen County into Lake Erie.

King’s Save Maumee Riparian Buffer Initiative projects are made possible through the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) and the U.S. Forest Service.

From 2008 to 2016, her organization was even chosen to represent northeast Indiana’s waterways on Capitol Hill for Washington D.C.’s Great Lakes Days during Clean Water Week.

Today, King and almost 350 other volunteers with Save Maumee are addressing the challenges facing Allen County’s rivers in three main ways: protecting riparian areas, planting new trees, and removing invasive species.

First, they strive to protect and increase riparian areas that can help improve the health of the Maumee River by minimizing runoff and erosion.

Riparian areas, such as the Trier Ditch, the Six Mile Creek, and the Bullerman Ditch in East Allen County, all help filter out pollutants in the waterways that eventually “feed” into the Maumee, and the Maumee Watershed is the largest watershed feeding into the Great Lakes, so its impact goes far beyond northeast Indiana.

Along with protecting these natural filtration areas, the organization plants more trees to improve water quality, as trees and plants provide nourishment and shade necessary to the health of streams. Vegetation also helps control flooding, creates habitats for wildlife, restricts the flow of soil during heavy rains, and filters water deep into the soil, King says.

Finally, Save Maumee focuses on removing invasive species from the riverbanks, such as the Asian Honeysuckle, and thus, allowing Indiana’s native species to pollinate and thrive. Invasive species, like the Honeysuckle and ornamental pear trees, are a serious threat to the health of northeast Indiana’s waterways, King says. They often threaten larger trees and can end up sterilizing natural species.

She and her team activate removal projects to rid the riparian regions of these—and other— threats.

According to an Alliance for American Fish and Wildlife study, 33 percent of all U.S. species are at risk of becoming endangered, and it’s vital to society and the environment to have a balance of species. So making northeast Indiana’s natural environment a healthier place for wildlife impacts everyone.

“In 2011, one-third of Lake Erie died,” King says.

She explains that it was due to harmful algae blooms that could have ultimately destroyed the entire lake if the federal government not acted to help improve the lake’s water quality.

“We’re fortunate,” she says, “that Allen County has more water than it knows what to do with.”

But that’s why it’s even more important to protect local waterways from the kind of potential disaster that struck Lake Erie, King says.

As northeast Indiana develops to attract businesses and talent to the region, trees are being removed for human interests, such as commercial developments, timber value, energy easements, and eminent domain.

They might pose a threat to power lines or levees that prevent river overflow. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers mandates that all vegetation must be removed 15 feet on either side of all levees.

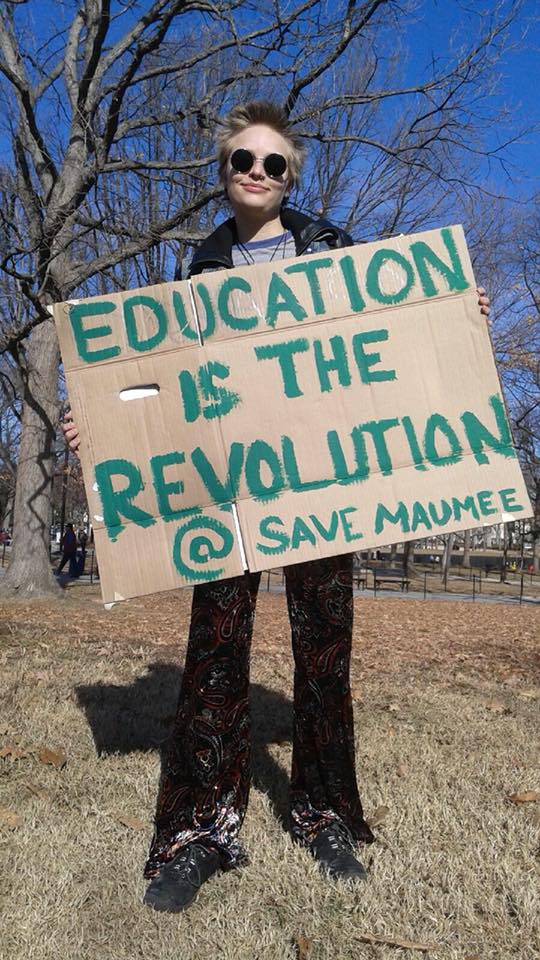

Anna Gurney, the New Haven-Adams Township Parks Dept. Recreation Director, agrees with King that public education is a necessary component of saving our rivers, streams, and native plants or trees, as the region develops.

The more citizens are aware of their environmental footprint and its impact on local species and places, the more they will support grassroots efforts to protect and preserve our trees, ditches, and streams, Gurney says.

In September, Save Maumee Grassroots Organization will sponsor a community clean-up campaign where citizens are invited to participate in their work.

As Phase 1 for Fort Wayne’s Riverfront development plan is underway, King encourages planners to emphasize ways for expanding and upgrading our natural environment.

She cites reports that predict “world water wars” are expected to begin as early as 2030, due to an extreme need for water in 47 percent of the world.

To help combat these challenges on a local level, her organization has already planted 2,780 trees along 1.4 miles of stream bank that starts at the Maumee and flows all the way to Woodburn.

It is up to the public to get involved in the desperate need to protect and preserve northeast Indiana’s watersheds and water habitats, King says.

While businesses come and go, waterways and wildlife are here to stay, and without them, mankind cannot exist.

Help Save the Maumee

For more information about Save the Maumee’s work or to get involved with the organization, contact King at (260) 417-2500.