Think Downtown Fort Wayne needs better parking? The solution might be public transit

It’s time to change the conversation from “more convenient parking" Downtown to “more accessible public transit.”

I’m sitting at Utopian’s patio on The Landing one morning, asking why it is: Why does it feel inconvenient to park and walk a few blocks in Downtown Fort Wayne?

It just took me 10 minutes to park and arrive at my destination. The closest garage was full, and most of the street meters nearby were bagged off for construction. I found a few one-hour spots, but I needed more time.

I eventually settled on a two-hour meter three blocks away and showed up to the table huffing, flinging my bag over my shoulder, apologizing for being late.

“It was hard to find parking,” I say, absentmindedly.

It’s an odd complaint, if you think about it. I’ve previously lived in Manhattan where I didn’t even have a car because it was too expensive and inconvenient to park. I regularly walked 20 minutes to the subway each morning on my commute. So why does more convenient—and much more affordable—parking in Downtown Fort Wayne still feel like a hassle sometimes?

It’s a question Frank Howard and his team at Downtown Fort Wayne pontificate about whenever they’re confronted with resident complaints about parking. As Downtown has grown and developed in recent years, much of it has received positive marks from the community. But parking remains a persistent challenge in the public’s eyes—or perhaps, more accurately, it’s a perceived challenge.

A summer 2021 survey of 475 young adults, ages 21-35, in Allen County found that more than half (58 percent) say they “would go Downtown much more often if more convenient parking were available.”

It’s findings like these that keep city leaders, like Howard, scratching their heads.

“It can be a difficult conversation to have as a community, but it’s an important one,” Howard says. “If we compare parking in Downtown Fort Wayne to other midsize to large metropolitan experiences, it’s actually very reasonable, very accessible, and there’s an abundance of spaces.”

As Director of Operations for Downtown Fort Wayne, Howard hosts monthly parking meetings for representatives from several Downtown entities. They discuss parking challenges and adjustments due to upcoming events, festivals, developments, or road closures. They even update a free printable parking map of Downtown each month, courtesy of Visit Fort Wayne. The map shows 25 public parking garages and lots clearly marked and scattered throughout Downtown. It lists prices and hours for each location, most charging $1 an hour with a daily max of less than $10.

Street meters aren’t listed on the map, but there are 800 of them, including 25 accessible or handicapped parking spots. They cost a flat rate of $1 an hour, too, and if you’re parking anytime other than 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays, the metered spots are free.

As many visitors to Fort Wayne can attest: Parking is actually quite accessible here. Events Manager at the Allen County Public Library Leanne Bure says visitors to its acclaimed Genealogy Center are frequently stunned by how affordable parking is at the library’s three lots.

“We have national guests who use the Genealogy Center, which is the second largest research collection in the U.S., and to them, $1 per hour parking (capped at $7/per day) is just unheard of,” Bure says.

This resonates with Emily Stuck, Director of Visitor and Partner Services at Visit Fort Wayne. She says parking is one of the most imperative things her team makes available and known to visitors upon their arrival. And once visitors learn about parking here?

“We hear really positive feedback,” Stuck says. “When you’re visiting a community, you’re often absorbing knowledge, and you tend to be more open to new experiences. Visitors appreciate the rates in Fort Wayne and the different parking options available to them Downtown.”

On the other hand, it’s full-time Fort Wayne residents who often complain about parking Downtown.

“People in small towns and rural communities just expect free parking, at a surface lot, right in front of their destination,” you might assume. And that is often the case. But the desire to park at one’s destination—and to complain about “bad parking” Downtown—is a phenomenon that plagues not only Fort Wayne, but also most cities across the U.S., particularly those reclaiming their Downtowns from the suburban sprawl of previous decades.

As residents return to urban areas that were vacated and/or demolished in the post-World War II automobile boom, they come back to cities boasting new developments with more-than-enough parking (often ensured by zoning codes). Yet, there remains a disconnect between urban parking infrastructure and how the public wants to use it—a byproduct of the pervasive friction between personal vehicles and the walkable, communal nature of cities. Combine this with woefully lagging public transit in many places, and it’s the perfect storm to concoct the misguided complaint: There’s nowhere to park Downtown.

The Downtown dilemma

Part of the challenge with parking in urban areas is that Downtowns, by nature, aren’t designed for vehicle transit so much as they are designed to be experienced by foot. Surface lots or stand-alone parking garages might increase convenience, but they also come at a cost to communities, aesthetically, experientially—even financially.

While lots and garages can generate revenue, they also create “dead zones” in cities, eating up scarce urban land, reducing density, and limiting the capacity to build other amenities many Downtowns need—like housing. Perhaps most poignantly, parking developments detract from the experience of what it means to “be Downtown” in the first place.

As cars became the main mode of travel in the U.S., many cities, including Fort Wayne, infamously demolished their historic buildings for the sake of expansive lots and garages—only to spend decades and billions of dollars later rebuilding what’s been lost. The Landing is one of Fort Wayne’s most iconic pedestrian-friendly blocks today, but you might be surprised to learn that it once stretched for not one, but five city blocks from Harrison Street east to Clay Street. Much of it was demolished to make way for parking.

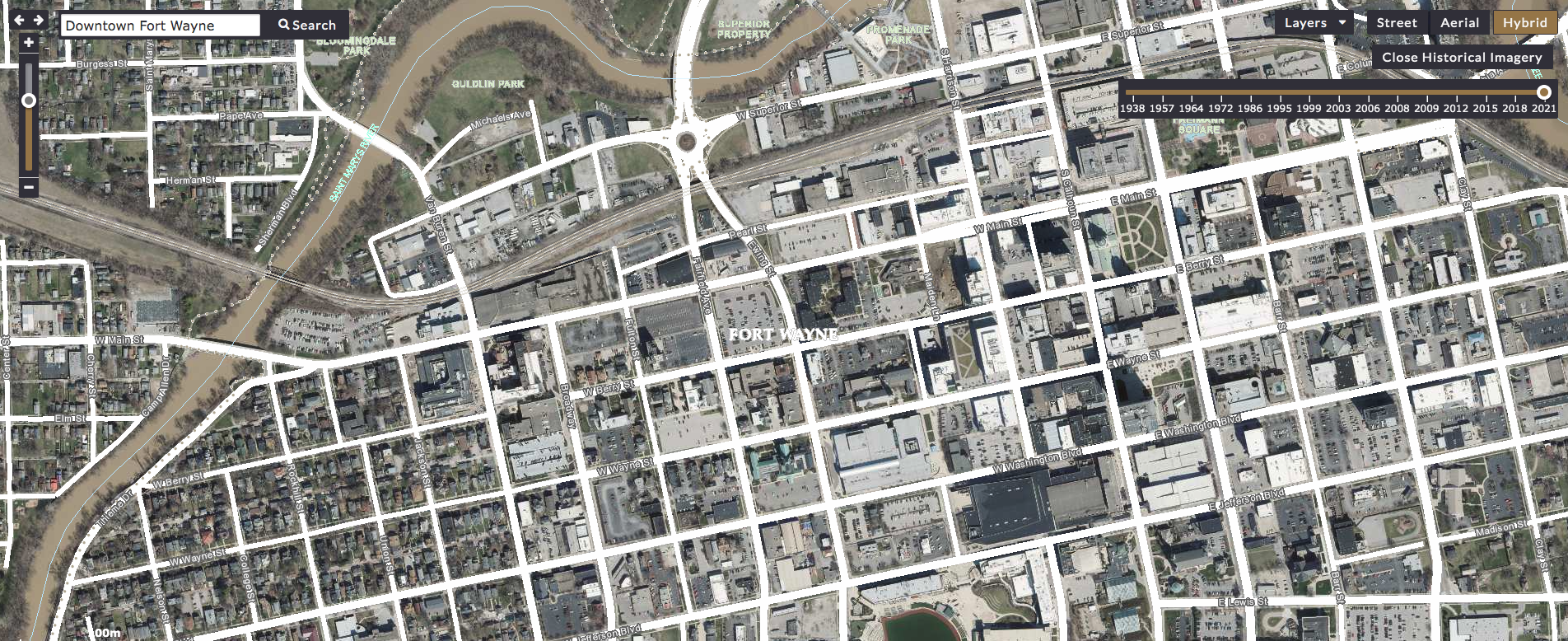

Aerial views of Downtown, courtesy of the iMap Allen County GIS Data Viewer, are telling.

The Landing:

Downtown as a whole:

In an article for the Atlantic called “How Parking Destroies Cities,” Michael Manville an Associate Urban-Planning Professor at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, makes the case that satisfying the demand for “more convenient parking” Downtown often hurts more than it helps. In fact, designing cities for vehicles, rather than people and public transit, is what makes the experience of parking and then walking to your destination Downtown feel less enjoyable, than say, walking to the subway in New York.

“The short walk to a Manhattan subway stop will take you past attractive store windows, which come right up to a sidewalk largely uninterrupted by driveways,” Manville writes. Whereas in cities designed for cars, “you’ll get a good view not of stores but of their parking lots.”

What’s more, City Monitor reports that providing more parking Downtown doesn’t even reduce the need for it. Instead, it actually increases the problem, tripling the likelihood of people to own cars and widening the distance between buildings, thus, “increasing the need to use cars to move around, which, of course, spurs the need for more parking.”

So is more parking in Downtown Fort Wayne actually what we want?

You can’t always get what you want

As use of the personal automobile and demand for parking has increased in cities, it’s resulted in solutions to satisfy these demands largely focused on street meters and parking garages. But the way these infrastructures are intended to function and how drivers actually want to use them are often out of step.

Let’s start with curb parking and street meters. Research finds the seemingly Midwestern desire to park on the street in front of your destination is actually a basic human desire for convenience.

“Because curb parking is convenient and usually free, drivers fill up the curb first, no matter how much off-street space exists nearby,” Manville reports.

But this tendency to choose street spots over garages can add to the frustration of urban parking for drivers and cities alike. In 1935, the first coin-regulated parking meters were invented in Oklahoma City to regulate curbside congestion created by automobile ownership among Downtown employees. Meters were intended to create a quicker turnover of cars at those coveted street spots, allowing retailers to reap the benefits of consistently open parking in front of their shops rather than lose those spaces to daylong parkers.

As manager of Fort Wayne’s street meters, City Clerk Lana Keesling says our own Downtown meters are still intended to have this turnover effect. That’s why they max out at one or two hours, and why they don’t make feeding the meter easier. It’s also what allows Fort Wayne to maintain its flat $1 an hour rate for street meters Downtown (a price Keesling says isn’t likely to increase anytime soon.)

Some cities offer long-term street parking with mobile apps where you can digitally “feed the meter.” They regulate how long you stay, not by limiting your time, but by charging more per hour. Even so, Keesling believes, in many ways, allowing long-term parkers to claim street meters defeats the purpose of meters in the first place. If people want to park longer, they can go to the equally (if not more) affordable garages nearby.

Still, a lack of long-term or easy-to-feed meters might contribute to public annoyance with parking Downtown and make drivers leery of violations (even if a parking ticket typically costs $10 in Fort Wayne).

Growing pains

Another part of the challenge with parking in small or mid-sized cities, like Fort Wayne, is adjusting your expectations. When you go to a “big city,” like Chicago or New York, you expect to pay for parking; you expect to walk and encounter obstacles, so it doesn’t feel like a bad deal. On the other hand, when you’re driving around a smaller, Midwestern community all day, you get comfortable with convenience; anything beyond it feels worse in comparison.

In many ways, Fort Wayne is still growing into its Downtown, too. From 2017 to 2019, Downtown was experiencing some growing pains, and parking was getting tight, Howard says. Since then, he notes that garage expansions, new construction, and creative partnerships have largely resolved the issue. There’s still some congestion near the Riverfront and The Landing this summer (which likely caused my own parking challenges near Utopian). But these issues are temporary, as construction on the Riverfront and Pearl Street continues.

After all, plans for Riverfront development include at least two new mixed-use parking garages. The office and retail development, Riverfront at Promenade, across from Promenade Park, conceals within it a 950-vehicle (and weather-controlled) garage. About 500 of its parking spots are already open. Another mixed-use residential development, Headwaters Lofts, is rising on the former Club Soda parking lot with an estimated 650 parking spots when it opens in 2024.

Keith Thornton, Community Development Manager for the City of Fort Wayne, oversees parking garages and contracts for the Redevelopment Commission. To give an idea of just how much parking capacity has expanded in recent years, he offers some numbers.

“Back in 2016, the Redevelopment Commission alone managed about 2,400 parking spaces Downtown,” Thornton says. “By the time Lofts and Headwaters Park garage opens in 2023, that number will have grown to more than 5,500 spaces. And that doesn’t take into account the private- or county-owned parking developments Downtown. So there’s certainly adequate parking in Fort Wayne.”

Even so, while these developments are likely to more than satisfy Downtown’s need for parking on paper, history has proven that garages—no matter how numerous—are unlikely to alter public sentiment about how “convenient” it is to park Downtown. As Manville explains in the Atlantic, “minimum parking requirements” have been built into the zoning regulations of many cities, mandating developers include a certain number of parking spots in projects. This often takes shape in the form of on-site parking garages. And yet, even these mandated and on-site parking palaces don’t quell the public demand for “more convenient parking.”

Instead, the cycle often goes something like this: People ask for better parking Downtown; cities supply them with convenient and space-efficient garages; people still complain about parking because they can’t find a curbside spot or a surface lot. Largely, it’s a lose-lose-lose scenario where people feel like they get “bad parking” Downtown; city leaders feel unseen in their attempts to make parking more accessible; and communities lose urban land to idle vehicles, increasing the cost (and decreasing the value) of being “Downtown.”

Thankfully, Thornton says Fort Wayne leaders, like himself, stay abreast of “the science of parking.” And while parking plays a role in new developments, the city doesn’t have hard-and-fast “minimum parking requirements” Downtown, as other places might. Instead, Fort Wayne has “general zoning guidelines” for the number of parking spots that should be accessible to new developments, and “accessible” doesn’t necessarily mean “attached.”

“Generally speaking… we hope to gain no-less than the number of spaces that were lost as part of the development,” Thornton says. “In a residential mixed-use scenario, a ratio of 1.5 parking spaces per dwelling unit is optimal. But there are unique situations where parking may not be part of the development agreement. There are very strategic approaches to these rare types of partnerships, and we have to consider if the gain of a new business, attraction, or habitable space outweighs the loss of the parking spaces, and can we increase parking availability in another location to support the development.”

Over the years, Fort Wayne has creatively kept up with the demand for parking by vertically expanding its Civic Center parking garage with 200 additional spaces, restructuring parking agreements to increase capacity in existing garages, and repurposing under-utilized spaces for parking, like railroad underpasses.

In coming years, Thornton says Fort Wayne is likely to see digital parking advancements at city-owned garages that will allow drivers to track in real time which garages have vacancies. This may eliminate some of the frustration in driving around to find a spot.

But perhaps the largest sign of progress is that parts of Fort Wayne are already willing to forgo cars and parking Downtown, in general. For example, Thornton says visitors and tenants along The Landing have been willing to sacrifice curbside parking and driving on Columbia Street to use it as a pedestrian-only space instead.

“Columbia Street has been largely gated off to traffic since it was redeveloped,” Thornton says. “It could be opened up, as needed, but it’s had such good feedback from the public and from tenants as a closed-off, safe, pedestrian zone, that we leave the gates down for the most part, other than to allow for truck deliveries.”

So what’s next?

Before the personal automobile, most Fort Wayne residents visited Downtown by street cars, buses, or other forms of public transit. Today, Fort Wayne’s Citilink bus system remains an option, but the frequency of its trips are limited and often far too time-consuming to make it a viable alternative to driving. But what if it could be?

If cities like Fort Wayne want to create walkable Downtowns that are welcoming to as many residents as possible, and if the current meter and garage systems largely aren’t satisfying public demands for parking, it only makes sense to offer transit infrastructure that allows people to enjoy urban spaces to their full potential. (Impending technology, like self-driving cars, and the environmental push for rideshare could make parking developments obsolete anyway.)

To make up for construction-related parking challenges this summer on the North side of Downtown, City Councilman Geoff Paddock (D-5th) says the developer Barrett & Stokely Inc. sponsored a complimentary shuttle service during some of the biggest Downtown events, like Three Rivers Festival.

“It’s a pretty generous service that frequently runs from Fourth Street near the Wells Street Corridor to the Three Rivers Festival Downtown,” Paddock says. “And so far, it’s gotten good reviews.”

This could be a sign of what’s to come—not just in Fort Wayne, but around the world. A study of parking inventory in Mexico City found that parking spaces accounted for 40 percent of all new development in the city.

“Between 2009 and 2013, 250,000 parking spaces were built, researchers found, costing about $10,000 per space,” City Monitor reports. “That money could have funded 18 lines of bus rapid transit, a system capable of moving 3 million people a day. The city responded by turning parking minimums into parking maximums, making sure new projects didn’t add to the excess supply.”

It would be interesting to see a similar study conducted in Fort Wayne. Maybe some of the funding and energy spent on parking Downtown could go toward solutions that have a better potential to meet people’s needs, like transit.

Urban parking is a constant balancing act of managing supply and demand, aesthetics and function, individual expectations and a community’s broader interests. A more long-term, economic, and environmentally conscious way to improve the system might be to reduce the need for it.

It’s time to change the conversation from “more convenient parking” Downtown to “more accessible public transit.”

See for yourself!

To access historic aerial views of Downtown Fort Wayne, visit the digital iMap Allen County GIS Data Viewer. In the upper right corner, click “Hybrid,” and then click “Historical Imagery View.” It will default to a 1938 map and offer a timeline in the upper right corner where you can scroll through the years up to 2021. You can use the search bar in the upper left corner to narrow in on specific addresses.

As you travel in time, watch how the use of land Downtown has evolved, turning from dense, building-lined streets into expansive parking lots and garages.

This story is made possible by underwriting from Design Collaborative.