‘A food crisis’: COVID-19 reveals gaps and opportunities in Indiana’s food system

“With this pandemic revealing the fragility of our current food supply chain, don’t you think it’s time the state of Indiana starts feeding itself?”

This story exploring how communities across the U.S. are evolving during the COVID-19 pandemic is made possible with funding from Google’s Journalism Emergency Relief Fund.

If you live in Northeast Indiana, you might know Joseph Decuis as a farm in Columbia City or a fine-dining restaurant in Roanoke. You might know about its casual Friday night burger events on the patio or its renowned Japanese-style Wagyu beef at the Joseph Decuis Emporium next door.

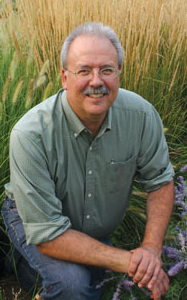

When Pete Eshelman and his family founded the business about 20 years ago, they intentionally designed it as a vertically integrated operation, partly to interact with customers at multiple touchpoints, as an event venue, a grocer, and a world-class restaurant.

Another reason behind their diversified model is that it allows Joseph Decuis to manage nearly every step of the process from pasture to plate, cattle to carry out, fostering a culture of support for a burgeoning local food movement in Northeast Indiana amidst a system designed to squelch it.

For decades, Eshelman has seen trouble mounting in Indiana’s ag sector as farms have expanded and specialized to fulfill industrial demand for raw commodities and exports, rather than feed Indiana households. Public policy has favored efficiency and expansion, too, decreasing the value of food and making mid-sized, diversified farms nearly extinct.

While no one could have prepared for the havoc the COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked upon the world, Eshelman knew it was only a matter of time before something disrupted the state and national food supply chains, leaving consumers in the lurch.

So when prices started rising at supermarkets and shelves were suddenly bare of dietary staples like meat and produce, it was no surprise to him. Joseph Decuis has been able to roll with the punches and keep serving customers throughout the pandemic, but for many Indiana farmers who rely heavily on the state’s outsourced food system, that is not the case.

“The food system is built on stilts,” Eshelman says. “When something hiccups, the whole thing crumbles, and that’s the reality. We’re not only in an economic crisis, but also a food crisis.”

Take meat processing, for example.

One step that Joseph Decuis doesn’t manage in getting its food from farm to table is processing meat, and that’s where challenges lie for many farmers during COVID-19. Since a handful of large corporations have a monopoly on meat processing in the U.S. and many of these large plants have been shut down or impaired by virus outbreaks, the processors left are being overwhelmed by national demand. This is forcing farmers to euthanize or abort ready-to-harvest animals.

Eshelman says the meat processor he relies on for his Wagyu beef in Michigan is “going gangbusters” right now, but thankfully, he’s been able to stay on as a client due to his longstanding relationship and his small orders.

“We’re not processing hundreds of cattle a week,” Eshelman says. “We’re only processing four to six per month for the Emporium.”

This low quantity qualifies him as one of the “little guys” in the global beef game. And perhaps what COVID-19 is showing Indiana is that there’s more room for little guys to rise up and fortify the state’s food faltering scene—growing, raising, and processing food in-state to fill the gaps left by larger firms that have experienced worker illnesses and reduced operations.

While a local food movement has been slowly gaining strength in Indiana for 45 years, it is often dismissed as “too small to matter.” Eshelman believes the pandemic is shifting the conversation in a productive direction, revealing that a commodity system alone cannot effectively feed Indiana residents.

When disaster strikes, Hoosiers need more sustainable and localized food sources, he says. And now, in this season of disruption, there is room for innovation—particularly in states like Indiana that are commonly considered among the world’s “breadbaskets.”

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Eshelman says. “A lot of farmers can’t be in this situation—where they’ve raised animals and crops, and they have nowhere to go.”

‘Get big or get out’

While Hoosiers might think of Indiana as a farm state due its quaint red barns and vast stretches of cornfields along country roads, Indiana farms are feeding commodity markets more than Hoosiers. But it wasn’t always this way.

In the early- to mid-1900s, small family farms thrived in rural communities across Indiana. Then in the post-World War II era, the state’s agriculture scene drastically changed as advances in chemical applications and machinery made it easier to mass-produce crops. Heavy-handed public policies began to favor the large industrialization of production at the expense of the needs of household consumers, too.

These changes were ushered along by leaders like Indiana’s own Earl Butz who served as Secretary of Agriculture for Presidents Nixon and Ford and was famous for his “get big or get out” philosophy of farming and calling for farms to plant “fencerow to fencerow.”

According to data from Indiana University, the number of farms in the Hoosier state dropped 70 percent between 1925 and 2014 as the average size of farms more than doubled. But while this shift may be startling to see in numbers, the way it played out has been more subtle. Many of the larger farms are still technically family farms and family-owned businesses, even though they produce raw materials for processing instead of food for residents.

Today, Indiana ranks fifth in the nation for corn production, which is largely used to feed animals or worse—feed into the global demand for corn byproducts, like ethanol and high-fructose corn syrup.

In fact, every dollar spent on farm commodities in Indiana effectively requires consumers to spend another dollar on the medical care needed to treat diseases, like diabetes, that a poor diet and lack of exercise are causing, says Ken Meter, President of the Crossroads Resource Center in Minneapolis.

“The amount we pay for treating diabetes is $327 billion per year, while US farmers sold $388 of commodities in 2018,” Meter reports.

As a former journalist-turned-food-systems expert, Meter has worked to create policy change that promotes more sustainable agricultural systems since the mid-1970s. He says his work is not necessarily about criticizing large-scale systems; it’s more about questioning the resiliency of current food systems and asking if there’s a better way to design systems that meet the true needs of consumers and reflect the uniqueness of diverse regions.

“I’m interested in how people in places like Fort Wayne can make better decisions about their lives and determine what is the best food system to have,” Meter says. “Right now, Northeast Indiana is putting most of its resources into a failing food system.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as large plants with workers shoulder-to-shoulder become hotbeds for the virus, many long-overlooked problems of a profits-at-all-costs food system are coming to light.

“It’s really showing us the limits of getting large, running a business strictly on the basis of cutting costs, and thinking solely about efficiency,” he says. “Firms have to be operating at a scale where they can care about people, health, and wellness. Most smaller plants have been able to do this.”

Over the years, Meter has conducted research in 144 regions across the U.S., as news about his work travels by word of mouth. In 2012 and 2016, he was hired to do two studies in Indiana. The first was a statewide study commissioned by the State Health Department to examine the impact that Indiana’s agricultural practices are having on health. The second study was commissioned by the Northeast Indiana Regional Partnership to develop a strategic plan to support a local food network here.

While Northeast Indiana has long been home to family farms and farmers markets, there have been few coordinated efforts to chart the major players in the local food network and examine how they interact and contribute to the region’s economy.

“It sounds silly to say it, but farmers are businesspeople, too,” Meter says. “Leaders in Northeast Indiana are realizing that they should be reaching out to farmers in a better way.”

As such, the volunteer-run Northeast Indiana Local Food Network has emerged out of the Partnership’s efforts to link farmers and food manufacturers. But while regions like Bloomington and Northeast Indiana are making progress in supporting farmers and locally produced food, Indiana, as a whole, still has a long way to go.

In Meter’s 2012 study, he pointed out a damning statistic that Hoosiers spend roughly $16 billion per year on food, yet more than 90 percent of these expenditures are going to farmers and producers out of state—even out of the country. When it comes to fruits and vegetables, 98 percent are imported.

“And that’s a conservative estimate,” Meter says.

Meanwhile, Indiana farmers only sold about $11 billion of commodities, mostly for export.

This imbalance isn’t unique to Indiana. Among the food systems Meter has studied across the U.S., Vermont has one of the most advanced local food economies he’s seen.

“They’re about 30 years ahead of where Northeast Indiana is today,” he says.

Yet, even Vermont only grows and sells about 5-6 percent of its own food in-state.

The question local food advocates, like Eshelman, are asking is: What could Indiana’s ag sector look like if even 10 percent of the money residents are currently spending on out-of-state food was redirected to food produced by farmers in-state instead?

“That would instill about $2 billion of revenue in agriculture in Indiana and help people be more food independent,” Eshelman says.

Keeping the money in-state would have trickledown effects for the economy outside of the ag sector, too. According to research by Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, personal income rises by 22 cents for every $1 increase in agricultural sales in-state over the course of five years.

On top of that, communities—even food deserts—would be better prepared to feed themselves in the face of a global crisis.

“With this pandemic revealing the fragility of our current food supply chain, don’t you think it’s time the state of Indiana starts feeding itself?” Eshelman asks.

But shifting to a more robust, local food economy in the Hoosier state will require broad, systematic change—not to mention meddling in some messy, time-intensive Indiana politics.

‘The state of Indiana tried to shut them down’

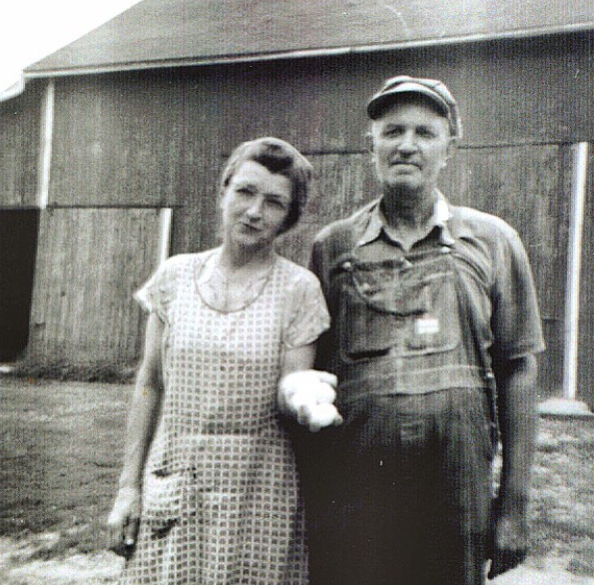

On paper, the Hawkins Family Farm and processing plant in Wabash County seems like everything the Hoosier state is about: Small business, family values, even an undertone of Christianity.

As a third-generation farmer, Jeff Hawkins inherited the land from his grandparents, and after serving as a parish pastor for several years, he began hobby farming with his family in 1988, following sustainable, regenerative practices. In 2003, he began farming fulltime, transferring his ministry from the pulpit to the fields, where he now invites people from all over the world to learn how to produce food sustainably.

The Hawkins Family raises poultry, hogs, cattle, and vegetables and processes their own chickens on-site, using better-than-organic practices. But in the mid-2010s, they got tangled in a long legal battle that nearly cost them their business.

“The state of Indiana tried to shut them down,” says Eshelman, who got pulled into the fight, too, since he serves Hawkins premium chickens at his restaurant and Emporium.

Here’s what happened.

In August 2014, Hawkins expanded his on-site chicken production facility, complying with Indiana law, so he could sell chicken to restaurants. He purchased more than $50,000 of processing equipment and hired seven new employees to process roughly 2,000-3,000 poultry per year.

While the Indiana State Department of Health initially challenged his expansion, he was granted an exemption by the Indiana Board of Animal Health (BOAH) in April 2015. This exemption allows small farms producing under 20,000 birds to sell on-farm processed poultry to restaurants without the costly amenities required for USDA inspections, like laundry service for inspectors’ frock coats and rent-free office spaces.

In other words, the BOAH exemption is designed to give small-to-mid-sized processors a safe way to get in on the processing game at a level they can afford, and by 2016, Hawkins Family Farm was the only farm operating under that exemption in Indiana.

But as a blog by the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund puts it: “For Big Ag and its allies, that is one farm too many.”

In January 2016, HB 1267, authored by Reps. Don Lehe and David Niezgodski, received a hearing by the Indiana House Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development, seeking to strike down Hawkins’s exemption and take away his restaurant business under the premise of “a food safety effort.”

The trouble was, Hawkins had data to prove that his methods for processing chicken are statistically safer than USDA-inspected methods. On top of that, similar exemptions to the one he enjoyed have been safely and successfully used by thousands of other farmers around the country with no recorded cases of foodborne illness traced to small-scale poultry producers.

Along with arguing their case in court, Hawkins and Eshelman took it to the public via a social media campaign using the hashtag #keepchickenonthemenu.

While the restrictive bill did pass, the matter caught the attention of then-Gov. Mike Pence’s office, who directed the Lieutenant Governor to gather stakeholders and try to come to a reasonable outcome. Ultimately, they were able to reach a scale-appropriate agreement that would allow the Hawkins family to continue selling to restaurants with some additional safety measures and labeling requirements in place.

Even so, Hawkins says that the lengthy legal battle taught him a few things about being a farmer in Indiana. First, many small farmers would not have the resources and time it took him to fight for his rights—or the support of community members who were roused to act.

“We got lucky,” he says.

He also discovered that facts were poor arguments in support of his position. What ultimately turned the tides on HB 1267 was public perception and the blistering outrage his political opponents received on social media.

“When we demonstrated that (our way of processing chickens) was statistically safer than inspected processing our argument didn’t matter,” Hawkins says. “It was only when a threat was perceived politically that things began to move.”

Just as social media pressure can be an effective change agent for small farmers and producers, so can empty shelves at grocery stores.

‘We’re not quite as crazy anymore’

For decades, Greg Gunthorp feels as though he’s been seen as the rebel, granola-crunching hippie farmer in LaGrange.

Whereas Purdue Extension says family farms need at least 1,500 acres to operate sustainably, Gunthorp’s family of five has been doing it all on a mere 260 acres by selling directly to customers with disposable income. They own a vertically integrated operation, raising crops and livestock, processing them respectfully on-site, and preparing them for various markets and high-end restaurants. Chicago’s famous Chef Charlie Trotter and the Chicago Cubs buy their choice meats, just to name a few.

While Gunthorp only processes about 12,000 chickens and hogs annually, he made the leap to make his processing site USDA-certified when he built it in 1998. USDA recognition is far more expensive than Hawkins’s operation, but one that sets an example for other small family farms to follow. Even so, operating a small farm and processing plant is not easy, Gunthorp says, particularly when it comes to finding skilled labor.

Respectfully butchering and processing each animal on the farm requires forgoing much of the technology and machinery that makes larger firms efficient, so small processing firms end up requiring six to 10 times more manual labor than big plants do. On top of that, when the pandemic first hit, farmhands and processing plant workers—who are already overworked and underpaid—were stretched to their limits.

When restaurants and institutions closed in mid-March, Gunthorp’s team shifted to packaging more meat for retail. This change added more steps to the process, like cutting meat into smaller portions and labeling it. While his employees usually finish at noon on Wednesdays and take Thursdays off, they spent several weeks working straight through Thursdays until midnight or 1 a.m. Then waking up at 7 a.m. the next day and doing it all over again, while staying alert to social distancing.

As of early July, Gunthorp says his team is getting back to their regular hours, but it’s come at a cost. As restaurants struggle to stay open during the pandemic and as consumers stop hoarding food, his sales have slowed tremendously.

“This week, I’ll be below pre-COVID levels,” Gunthorp says. “I’m starting to get a little worried actually.”

Among the farmers he knows, those who primarily sell to retail operations have enjoyed steady business throughout the pandemic, but for those in the wholesale business, like himself, it’s been a rollercoaster riddled with a lot of uncertainty. He attributes the lower sales now, in part, to the lower profile of the national food crisis compared to other crises the nation is facing—from COVID-19 to rising racial tensions and a heated election year.

“People don’t pick up the newspaper and see the front page saying that the food supply is faltering and broken,” he says.

At the same time, he’s hopeful that the pandemic is still making consumers and politicians alike more uncomfortable with their current food supply chain to the point that they actually change it.

As an advocate for local food systems with the National Farmers Union, the Organization for Competitive Markets, the American Grass-Fed Association, and the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, Gunthorp has faced opposition to the notion of change in the past. But he’s seen positive momentum lately from politicians in Washington, D.C., as a result of the supply chain problems the pandemic is exposing. Even those who have historically supported the commodity system are starting to see value in supporting small farms and processors now, too.

“A few months ago, a large portion of the politicians and land-grant universities thought we were crazy hippies,” Gunthorp says. “We’re not quite as crazy anymore. It’s no longer a matter of telling people how messed up the food supply chain is; Now, people can see it.”

Empty shelves at grocery stores have been eye-opening for consumers, too, who might not have realized how much of the meat they purchase at their Indiana supermarkets is actually raised and produced overseas.

“I feel like the emperor no longer has any clothes,” Gunthorp says.

To prevent food shortages in the future, he’s advocating for more domestic production in Indiana and other states to establish more diverse and secure food supplies.

“By and large, we have to produce our own food,” he says. “Indiana does a really good job of producing raw commodities. But as we’ve seen this year, that doesn’t mean you have milk in the grocery or meat on the shelf. I think small processors and niche farmers can play a big role in changing that.”

But if the food supply chain does shift to support more small, local farmers and processors, consumers may see an increase in prices, as well. While specialty products like Eshelman’s Wagyu beef will always be expensive for their rarity, even basic locally raised fruits, vegetables, and meats will cost more than what Indiana consumers are accustomed to paying for national and foreign products.

That is, in part, because the national food industry has grown by outsourcing production to places where the land and labor are cheaper and by intensely cutting margins at every turn, Gunthorp says. Now that these abuses have lowered prices for consumers, American standards for what food should cost are lower, too.

When it comes to purchasing food to eat at home, Americans spend less of their annual household income on food than any other developed country, averaging only 6.4 percent per year, according to the US Department of Agriculture. In the early-1900s, when there was a robust local farm community, Americans spent nearly half of their income on food alone.

“As a nation, the U.S. has gone too far down that path of assuming that food should be really, really cheap,” Gunthorp says.

But while investing in local food may technically benefit farmers and consumers alike, many Hoosiers simply can’t afford to pay more for their food period. Meter pointed this out in his 2012 study, noting: “More than one of every four Hoosiers earns so little that they are in jeopardy of not eating well—a remarkable statistic in the nation’s tenth-largest farm state.”

Therein lies the conundrum.

‘The typical rules are open for change’

In the past several years, Meter says he’s seen positive movement in Indiana and other states around supporting local food networks and farmers. His own statistic that 90 percent of Indiana’s food comes from out-of-state has been quoted back to him several times by politicians, suggesting that there’s interest in change.

“There’s a lot of lip service that we should make this different,” Meter says. “But it’s really difficult to do.”

Despite the rising popularity of local and organic food, barriers to making the transition to a strong local food economy are complex for any state, Meter says. It’s not just politics that will have to change to balance the interests of corporations with local farms and processors. You’ll also have to change the food distribution networks and get grocery stores and consumers to pay higher prices for products. Either that, or products and services that support local food networks will have to be subsidized.

“That’s where political leaders get cold feet,” Meter says. “They don’t want to commit public money to making it easier to buy food from local growers, but they don’t mind spending public funds to subsidize exports. How we spend our public money determines what will happen. That is why efforts, like Jeff Hawkins’s, to insist that regulation doesn’t place him at a disadvantage are so important.”

For years, Indiana and other states have invested in infrastructure and tax breaks that support large-scale corporate farms and processors. If states are going to have successful local food systems, they’ll need to invest in local food networks to make them as efficient as possible, too.

“Existing infrastructure is fully adequate to handle large-scale shipments of food commodities to other places,” Meter says. “What Indiana lacks is infrastructure supporting local food trade. Such investments are proper for the public sector to make.”

In his 2012 study, he notes that one reason local food movements often fail is because they rely too heavily on commercial enterprise alone to resolve the issue.

“Educational initiatives, engaged citizens, and public policy will also play a significant role,” he says.

Networking among local food-related businesses and creating intentional industry clusters can help stabilize food economies, too. In Northeast Indiana, the Local Food Network released a new, fully interactive Local Food Guide in July intended to inspire connections and sales.

Another sign of momentum Meter is seeing in Indiana is the growth of farmers markets. Between 2008-2012, the number of farmers markets in the state doubled from 50 to 106.

“What that suggests to me is that in all these rural communities where corn and soybeans are dominant, folks are looking around and saying, ‘We need more growers raising fresh vegetables,’” Meter says.

Across the U.S., he is seeing more consumers willing to pay farmers to sell directly to them, too, through programs like Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs) shares.

Meter says that during COVID-19, he signed up for his first CSA because his travel was curtailed, and he was unsure of grocery store supplies. Most CSA farmers in the Twin Cities quickly sold out in 2020 and are wondering how to plan for 2021.

“That’s a real indicator of the interest people have in establishing a better connection to the grower and knowing where their food comes from, which is, ironically, really hard to do in Indiana,” he says.

While COVID-19 continues to throw the world into chaos and reveal broken systems, it also carries with it the possibility of a better future.

“As tragic as this crisis is, it does create a situation where the typical rules are open for change,” Meter says.

For champions of the local food movement in Northeast Indiana, emerging from the pandemic is not necessarily a matter of getting “back to normal,” it’s about figuring out what the “new normal” should be.

Eshelman says he doesn’t expect COVID-19 and other viruses like it to go away anytime soon, so he’s leaning into the diversity of Joseph Decuis’s business model, making sustainable changes like utilizing its restaurant staff to create locally sourced carry-out food for the Emporium instead.

“We were fortunate that we have a business model where we can immediately shift, and our business has really boomed,” Eshelman says. “People still want quality, locally raised food that they can take home for a good meal.”

Since the pandemic started, he’s seen his existing customer base shift with his business, and he’s attracted new customers who are realizing the value of local food for the first time. This gives him hope that a strong interest exists around supporting local food in Northeast Indiana; it’s now a matter of tapping into that interest and fanning the flame to build a brighter future.

“Therein lies the opportunity,” Eshelman says.