Partner Partner Content Are there enough college graduates in Northeast Indiana to sustain the economy we’re building?

A community’s ability to develop and retain college graduates is connected to its growth, how well blue-collar workers get paid, and how much social mobility it offers.

Driving around Downtown Fort Wayne, you’ll see a city on the rise. Construction is underway on several projects, including multimillion-dollar investments along the Riverfront and on the Electric Works campus nearby. Roads are getting busier. Streets feel alive on nights and weekends and at Saturday morning farmers markets.

But amidst the excitement of new developments, hip coffee houses, and a bustling brunch scene, Rachel Blakeman senses an elephant in the room—a question that keeps her up at night, as both a statistician and a homeowner. Is Northeast Indiana–-or Indiana, as a whole—doing enough to sustain Fort Wayne’s growth with its number of residents who hold bachelor’s degrees or higher levels of education?

“To the credit of city government leadership, they really have made a substantial investment in Fort Wayne’s quality of place,” Blakeman says. “But we need to talk more about the importance of education and bachelor degree holders in our economy.”

In an era where student loan debt regularly makes headlines and tech entrepreneurs are revolutionizing how learning can be done online, it might sound antiquated—even classist—to encourage students down the traditional four-year college path. Blakeman acknowledges that you might expect people, like herself, who holds a law degree and works for Purdue Fort Wayne’s Community Research Institute, to tout the values of higher education.

“But we don’t talk enough about the costs of not going to college for families and communities,” Blakeman says.

It’s a cost Mike Hicks, Author and Director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State, has written and spoken about extensively in recent years.

For starters, Hicks points out that while college degrees are expensive, they also contribute to higher wage growth throughout an employee’s lifetime. On top of earnings, college degrees correlate with other benefits on a population level, like longer life expectancy.

“For the average worker, the rate of return on a four-year degree is about $1.4 million over their lifetime,” Hicks says. “The wage premium of not going to college is about half of that.”

In other words, bachelor’s degrees are still largely the threshold at which wage-earners build wealth. Studies Blakeman has conducted for the Community Research Institute indicate higher education creates higher incomes on a population level. This, in turn, provides families with opportunities to save money and purchase homes—additional paths to generate equity and wealth over time.

The benefits of attracting and retaining college grads aren’t confined to degree-holders either. Instead, a community’s ability to develop and retain college-educated, high-wage employees and jobs also increases its social mobility and even improves how well blue-collar workers get paid. Investing in education leads to higher salaries, greater workforce effectiveness, and higher gross domestic product in states, too.

But while Fort Wayne is developing many quality-of-life amenities that might appeal to college graduates, Indiana as a whole continues to lag the nation in the number of bachelor’s degree holders it’s producing. This has crippling effects on the region and state’s economy, Hicks says. On the average year, he finds that Indiana “oversupplies its job market for non-college educated workers by about 15,000 kids each year, and undersupplies college graduates by about 6,000 kids.” Meanwhile, nationwide, about eight in 10 of all net new jobs go to four-year college graduates.

“The simplest economic argument for sending more Hoosier kids to college is that it is where the jobs of the future will be,” Hicks writes.

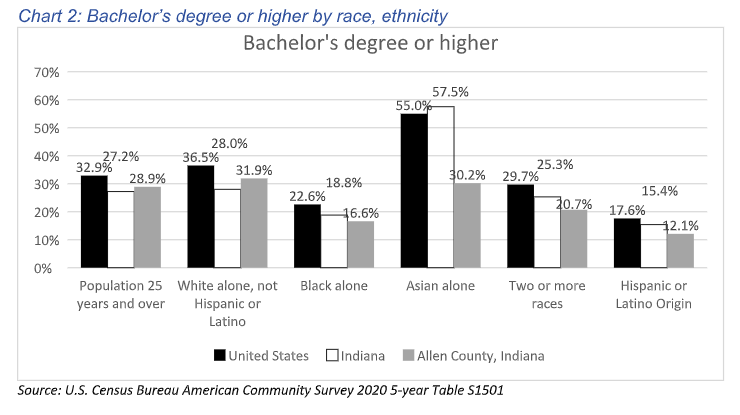

According to five-year data from the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey in 2020, Allen County’s rate of adults older than 25 with a bachelor’s degree (or higher level of education) is 28.9 percent. That’s higher than Indiana’s overall rate by 1.7 percent, but still lags behind the nation by four percent (32.9 percent).

In other words, Indiana and Allen County still have work to do to be considered “average” in terms of higher education attainment.

“Nationally, the places growing have 40-50 percent of the adult population with a bachelor’s degree or higher,” Hicks says. “This is why out of 92 counties of Indiana, about 60 are not growing, and 30, perhaps are growing, but most are still growing slower than the nation as a whole. It goes back to the proportion of adults who have a college degree because that’s where the job growth is.”

This is why economists and data-minded thinkers, like Hicks and Blakeman, get frustrated when they hear politicians and even educators in Indiana saying students “don’t need college” or encouraging them to go into the skilled trades instead of pursuing degrees. It’s not that trades jobs aren’t needed or can’t provide meaningful—even lucrative—employment for individuals on a case-by-case basis, Hicks says. It’s that, by the numbers and across the board, trade jobs are not where future job growth is happening in Indiana—or anywhere else.

“It sounds like a complex thing, but it really isn’t,” Hicks says. “What we have done in Indiana is over-emphasize the skilled trades as a viable option for students. We keep saying: There’s a demand for the skilled trades. When, in reality, we could replace every single skilled trades worker in Indiana today with kids who graduated high school a few months ago and aren’t going to college.”

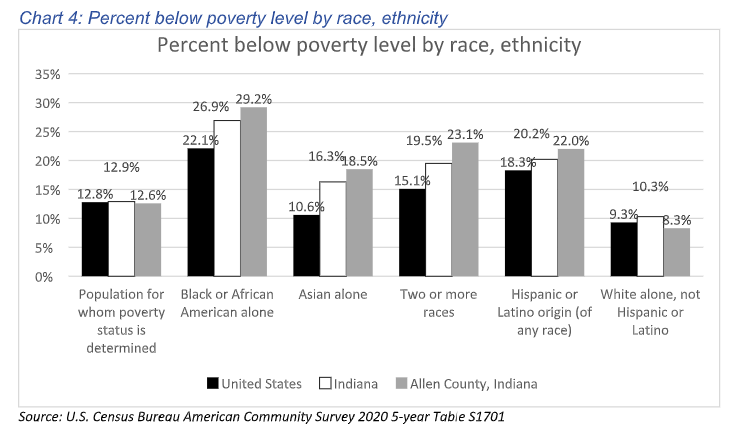

What’s more, while Allen County does slightly outpace Indiana in its educational attainment, Blakeman points out that these gains are confined to its white (non-Hispanic) residents. Outside of the white (non-Hispanic) population, Allen County has a higher share of people below the poverty threshold than both Indiana and the U.S. It also has lower rates of college attainment than the state or nation among Hispanic/Latino, Black, and Asian populations, as well as people of two or more races.

It’s these reasons Blakeman has given presentations about the value of college education at events, like the YWCA’s diversity dialogue, to help students and families understand the potential wealth they’re missing out on by foregoing college.

“It’s not that every single student in Indiana needs college,” Blakeman says. “But across the board, college is still the threshold for attaining most high-wage jobs and high-skilled positions and, as Mike Hicks has noted, the best way to boost wages for those without degrees is to surround them with more college graduates.”

On the average year, Hicks estimates that out of about more than 85,000 Hoosiers who turn 18 years old, Indiana can expect only about 25,000 college graduates per year to both finish college and stay in Indiana. He attributes the ongoing decline in college enrollment (and graduation) in Indiana to multiple factors, perhaps most notably the Indiana legislature’s dramatic funding cuts to the state’s budget for K-12 education and higher education. In 2010, Indiana’s legislature slashed inflation-adjusted funding to the state by about 20 percent on a per capita basis, which affects per-student spending as well as how much public schools and universities can offer in financial aid.

“The decline in state funding in Indiana for colleges and universities has really clobbered some of the most needy students,” Hicks says. “It’s to the point that, in this fiscal year, we’re spending less on a per-student basis for K-12 education and colleges than we were spending in 2010.”

Lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are impacting higher education’s desirability, too. As Hicks puts it, “The post-COVID labor market shock made it lucrative, particularly for young men, to make go into the workforce, make money, and defer college two or three years.”

It’s a decision he made himself when he enlisted in the U.S. army after high school. While he later went back to earn his degree, he warns Hoosiers of the challenges and risks associated with delaying higher education.

“The hardest thing I ever did was go back to school after eight years as an army officer, and leave a nice middle-class job to go back to school full-time,” Hicks says. “It’s tougher than being in combat.”

***

To help more students in Allen County achieve college degrees and empower the local workforce, R. Nelson Snider, a former principal of South Side High School in Fort Wayne, established the Questa Education Foundation in 1937. Today, Questa continues this mission by providing forgivable loans and scholarships to students in the 11 counties of Northeast Indiana pursuing a certificate, associate’s, or bachelor’s degree.

Elizabeth Bushnell, Executive Director of Questa, says in many ways, the organization is working to address the exact issue Hicks has highlighted.

“We’re focused not only on helping students achieve their education and making it more affordable, but also trying to keep graduates in the region,” she says. “Those talent needs Mike Hicks talks about are exactly what we’re hearing in individual conversations with local employers about how critical talent is to their success and growth.”

Questa achieves its mission by partnering with philanthropic organizations, schools, employers, and even individual donors who provide grants, most often to its Traditional Scholars Program. The program offers forgivable loans, up to 50 percent, if a student graduates college with a 2.75 cumulative GPA and lives and works in Northeast Indiana for at least five years after college. Since the program started in 2007, it has served more than 1,400 students and provided approximately $15 million in forgivable loans, Questa’s website says.

Bushnell points out that Questa partners with select schools in Indiana, too, and if students attend one of these schools, they’re eligible for up to 75 percent loan forgiveness, with the additional 25 percent funded by their school. Questa also has partnerships with regional employers, like Parkview Health, where if students enroll in school and commit to working for the employer after graduation, they can get 100 percent of their Questa loans forgiven, courtesy of their employer.

“It’s a fantastic way for us to help students overcome the financial obstacles that might prevent them from going to school or staying in school, and it connects them with a local employer early on, so they’ve got a job right after they graduate, and they can stay in our region,” Bushnell says.

In 2013, Questa expanded its program to include delayed start, returning, or current college students through its Contemporary Scholars Program. Even so, Bushnell says the number of students who apply for Questa programs and scholarships overall is still three or four times higher than the number of students they can accept. As the Journal Gazette’s editorial board noted in June, the number of college-bound students in Indiana continues to decline, too.

“Just 53 percent of Hoosier high school graduates went to college in 2020, marking a 6 percent decrease from the prior year,” the Journal Gazette reports.

Bushnell notes that while it’s tempting to pin this decline in college enrollment on the pandemic, this data is the latest in a ten-year decline, so it speaks to a longstanding trend in Indiana. One of the main factors she sees holding students and families back from college is the cost and perceived risk. About 70 percent of students nationwide rely on loans to afford college, and Questa has seen many students and families growing leery of loans, particularly as stories about insurmountable college debt have made headlines.

While the Biden Administration’s efforts to provide student loan forgiveness draw attention to the challenges associated with affording college, they also bring the cost—and risk—of college front and center in many people’s minds.

“There’s a lot of news about college debt right now, which is an important conversation, but I also think it feeds into a concern among students and families about whether college is worth it. However, the lifetime earnings of bachelor’s degree graduates is about $1.4 million higher than for those without a degree,” Bushnell says. “I’ve also seen throughout some of the data, there’s self-doubt among learners of all ages about whether college is right for them and whether they can do it. Without any guidance for students who don’t have family members who have gone to college before them, that can be a real barrier that can keep them from pursuing a college degree.”

This is one reason, Stephanie Smith, Assistant Director for Data and Marketing at Questa, says the organization is working to connect with families earlier in their students’ grade school education and demystify the financial aid terms in the college application process.

“The word ‘loan’ is very scary to a lot of people,” Smith says. “We see there’s a lot of resistance to even learning about the financial resources available to families because they’re scared, so we help them understand what they’re getting into. We don’t want people to be afraid of looking for assistance.”

Bushnell says, in many ways, Questa attempts to bridge gaps between high schools, colleges, employers, and families about what resources are available to make education more approachable. It also publishes a local database of scholarships available to students specifically in Northeast Indiana.

Another part of the challenge is helping students of all ages better understand the fluidity that often exists in modern careers.

“We tend to get stuck in a lot of either/or conversations, where it’s either the trades or college,” Bushnell says. “But the reality for most careers is that some post-secondary education is necessary, even in the trades. There are so many pathways to further your education, and they can connect with one credential leading to the next. There are resources, like Questa, that can make it possible.”

***

As Director of Communications for the nonprofit Northeast Indiana Works, Rick Farrant and his team focus on workforce development in the region, providing financial and employment resources for education and skills training. They oversee youth-oriented career development programs, fund and manage employer-focused training programs to enhance the skills of existing workers, and help facilitate community-based career pathway initiatives.

When it comes to educating and upskilling Indiana’s workforce to meet the needs of the modern economy, Farrant sees it as a complex challenge with a lot of moving parts.

“There’s some truth to the assertion that Indiana could use more college graduates, but I don’t think it paints the full picture,” he says.

He notes that while a college degree will always be required in certain fields and positions and while industry 4.0 focuses on automating systems and advanced technologies, there are still jobs within industry 4.0 where trades workers are needed to install, operate, and repair systems.

There are also employment opportunities and apprenticeships that allow workers to upskill on the job at no financial cost to themselves.

“If I am a worker and my employer offers a training program for me to be able to uplift my skills at no cost to me, I might take advantage of that; whereas, in the past, when we didn’t have some of these programs, a worker might have considered going to college instead to increase their skills,” Farrant says. “I don’t think any of these things are necessarily bad, but they may have impacted people choosing to go to the traditional college route.”

Northeast Indiana Works is a registered apprenticeship intermediary, which assists school districts and employers in providing apprenticeships for students and could lead to additional training or post-secondary education.

“If you look at the trade unions, who have 18 apprenticeships in Northeast Indiana, a lot are tied to two years of education at Ivy Tech,” Farrant says. “So throughout the course of an apprenticeship, which may be five years, students are earning money and getting training and education.”

He believes a key aspect of upskilling Indiana’s workforce is providing students with a broader palette of career pathways available to them at a younger age and encouraging them to choose what’s best for them.

“We are on the verge of launching three, web-based career awareness initiatives that I think will address getting people at a younger age to think about their careers and what it’s going to take to achieve them,” Farrant says. “These programs will likely help increase the college ranks, but also increase certifications or other forms of employment. We’re letting students know the workforce is changing, too, and that they need to have a higher level of skills to be competitive. The question is: How can a person best acquire those skills?”

When Farrant first got into workforce development about 10 years ago, he believes Indiana–and most of the nation—was actually overselling college education compared to other career pathways.

“I think one advantage we’ve had in selling more than one option for learning and training is, frankly, a lot of young people are going to be better trained than they would have been if the only option they saw was a traditional four-year college education,” he says. “I think we have to find this balance of: Yes, a college degree is a great thing, but so is a certification, and so is going into the military or starting a business. All of these things can be extremely helpful to the economy, at large.”

While national research generally confirms that higher educational attainment in communities correlates to economic growth, the conversation around what value colleges and college graduates bring to regions is nuanced. A study published in Brookings Institute finds that the “average bachelor’s degree holder contributes $278,000 more to local economies than the average high school graduate through direct spending over the course of his or her lifetime.” However, the quality of college they attend “greatly” affects the size of these benefits.

“College quality has major implications for the extent to which higher education boosts economic activity,” the report finds.

On the other hand, the quality of a college does not necessarily predict whether students will choose to apply their skills in the local workforce nearby that college after graduation. The same study found 68 percent of alumni from two-year colleges remain in the area of their college after attending, compared to only 42 percent of alumni from four-year colleges.

One challenge Farrant sees facing Northeast Indiana’s economy is its workforce population size. He notes that based on a study Northeast Indiana Works published in 2019, about 48 percent of high school and college graduates who attended school in Northeast Indiana leave the region within five years after graduation. This loss, combined with the region’s aging population, means Northeast Indiana needs more people in its workforce.

While Allen County experienced positive net population growth for the fifth consecutive year in 2021, and Fort Wayne clocked in as the second-fastest-growing metro in the Great Lakes region, Northeast Indiana encompasses 11 counties, most of which beyond Allen are rural communities. Across the state, rural counties are seeing more population loss than counties with metropolitan areas. As Hicks points out (and has been reported in the News Sun), rural counties also have lower rates of residents who hold bachelor’s degrees or higher.

In other words, population growth correlates with a community’s higher education attainment, too.

“Of the five (Indiana) counties that grew the most in the past decade—Indianapolis border counties Hamilton, Boone, Hendricks, Johnson and Hancock—all five had educational attainment levels higher than the state average, ranging from about 31 percent of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher in Hancock County to a state-high 59.3 percent in Hamilton County,” the News Sun reports. “Conversely, the five counties with the biggest population declines—Switzerland, Greene, Parke, Randolph and Pulaski counties—all have higher-education rates less than 15 percent, with Switzerland the lowest at just 10.9 percent of people holding a bachelor’s or higher.”

***

As Chief Economic Development Officer of Greater Fort Wayne Inc., Ellen Cutter and her team are working to advance the local economy, primarily by implementing the Allen County Together (ACT) Plan detailed on their website. Cutter says there are a few ways the ACT plan might increase the number of college graduates and high-wage jobs in the region, through job creation, entrepreneurship, and helping students identify career pathways, as well as engaging the business community in educational partnerships.

Drawing on Fort Wayne-Allen County’s position as an automotive manufacturing hub in the Midwest, the plan calls for creating 2,500 net new high-wage jobs by 2031 (or 250 per year on average) in the automotive technology sector. Cutter says these jobs will be focused in Industry 4.0 innovations, including electric vehicles (EVs), autonomous vehicles, and other advanced technologies on pace to disrupt the status quo of the automotive manufacturing industry.

Along with supporting the automotive tech sector, ACT calls for attracting and growing an additional 2,500 net new high-wage jobs by 2031 in research and development (R&D)-intensive, engineering-focused, and technology-driven growth industries. It also sets a community goal to launch a $10 million venture fund and accelerator by 2026 housed at Electric Works to enhance Allen County’s ecosystem for entrepreneurs, growing the fund to $25 million by 2031.

Looking to the future of Northeast Indiana, Farrant and Bushnell remain optimistic, particularly about collaborations happening to provide more resources to students and learners of all ages.

“There’s a lot of collaboration going on between regional employers and schools, colleges, universities, and nonprofits about career exploration for students and helping students find pathways and then identify the education they need,” Bushnell says.

One example she sees is the Region 8 Education Services Center recently received a grant from the Indiana Department of Education (IDOE) to aid Indiana’s schools and local partners in expanding students’ access to pathways leading to high-wage, high-demand careers.

“Another organization doing really great things to help students explore career options is Junior Achievement,” Bushnell says. “Part of addressing the value of higher education for students is giving them an idea of what they can do with a degree. The early career exploration JA provides is a tremendous resource to students.”

In September, Greater Fort Wayne Inc. hosted Hicks to present an outlook on the region at their 2022 GFW Inc. Economic Development Summit. Overall, he gave Allen County’s economy a positive review—with a warning to keep push for state-level reforms in education funding and stronger support for schools locally.

“Indiana could use about five more Fort Waynes in every aspect,” Hicks says. “There are very few places I visit with the mojo of opportunity and economic development working for it as you have in Fort Wayne.”

When it comes to developing, attracting, and retaining skilled workers, Hicks notes that a deficit of college graduates isn’t the only element threatening Indiana’s future. He points out that the state’s longstanding low-tax policies also hurt its economy and overall educational outcomes.

“It’s not just that we’re not getting kids to college, it’s that we’re also inviting businesses into our state that are less productive than the ones they’re replacing,” Hicks says.

While Indiana has long prided itself on being a “business-friendly” low-tax state, many of the state’s current tax policies favor goods-producing and -moving operations rather than high-skilled, high-wage jobs of the future. Meanwhile, across the U.S., people are largely moving from low-tax counties to high-tax counties, often to reap the benefits taxes provide, most notably being quality K-12 public schools.

“Business friendliness still matters, but business-friendliness in today’s economy is not low-taxes,” Hicks says. “It’s providing what modern workers want, like good schools. Taxes are the price of public services, so when you lower taxes, you’re investing less in local schools and amenities that ultimately make cities and states attractive.”

He notes that while “quality of life” tends to be measured by the public as a variety of “hip” factors urbanist Richard Florida describes in his 2002 book “The Rise of the Creative Class,” economists like himself measure “quality of life” with a stronger focus on the fundamentals: The first being quality schools, followed by a lack of crime and blight.

“The best evidence shows these are the things people care about most,” Hicks says. “Fort Wayne is working on these areas, and schools are an area where Fort Wayne can focus their thinking more to improve. It’s one thing to subsidize funky bars and coffee shops. But it’s really hard to make a school that’s sending kids to the Ivy Leagues every year. Fort Wayne is working on the complete package.”

A reason schools matter so much is that they not only produce talent for the 21st-century job market, but also attract talent to communities to reap the benefits of the school system.

“Schools essentially act both on the supply side of labor and the demand side of labor,” Hicks says. “That’s why we emphasize the importance of education quality as a component of economic growth.”

This article was made possible by underwriting from Greater Fort Wayne Inc. It is also part of a series on Economic Development underwritten by the NiSource Foundation, NIPSCO, and Junior Achievement of Northern Indiana, Inc.